Cole MacGrath is on a mission, sprinting down the raised train track as gunmen on both sides try to fill him with holes from the buildings across the street. He takes aim with his bare hand and fires bolt after bolt of electricity towards one masked enemy, still maintaining his sprint to close the distance. He makes contact, knocking the assailant out of their own shoes.

Cole jumps from the tracks, using his electric powers to glide through the air toward the ground below. Right before landing, he takes aim at the other enemy and lets loose three bolts of energy, with accuracy so precise it’s like time slowed to a crawl. That’s another shooter out of the equation.

That’s the sort of scene that plays out repeatedly throughout the 2009 open-world superhero adventure Infamous. A PlayStation 3 exclusive, the game dramatically changed the trajectory of developer Sucker Punch, ending the studio’s focus on cartoony raccoon thieves. The entire adventure is grim and gritty, the streets of Empire City—Infamous‘s version of NYC—are lined with trash, burnt cars, and encampments of people forced out of their homes. Its narrative is bleak: Explosions kill bystanders, defense contractors roll with armored vehicles to take control of the city. For Sucker Punch, previously known for games like the Sly Cooper series and Nintendo 64’s Rocket: Robot on Wheels, it was the first foray into more realistic territory. But Infamous wasn’t always the serious comic book game we ended up playing.

“The original idea for Infamous, believe it or not, was that it was kind of Animal Crossing, but you were a superhero,” Sucker Punch co-founder Chris Zimmerman said in an interview with GameSpot in 2014. Infamous, like most big-budget games, went through a number of iterations that included different powers and art styles over the course of it’s four year development cycle. “We worked on that for about a year in that direction. So much more stylized, much more cartoony than what you end up seeing. We worked hard to see if we could make that work.”

While some of the DNA from that early prototype made it into the final product, most of it was shed in favor of the Infamous we know today. EGM spoke to more than a half-dozen former Sucker Punch employees and gathered publicly available information from more than a dozen sources to find out more about the Infamous Crossing prototype, the studio’s original vision for the game, and why it changed direction.

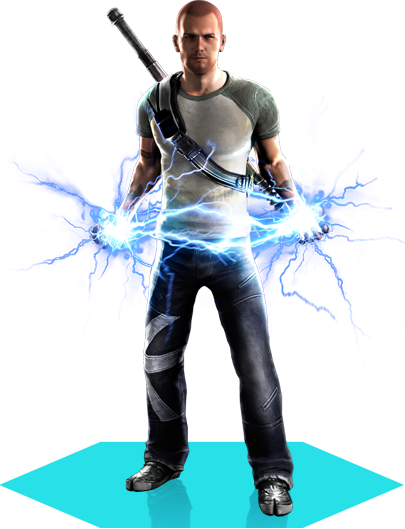

Credit: Sucker Punch, Sony

“An early concept was that the player made a hero, one that looked like it was from The Incredibles,” one anonymous source said, referring to the Pixar movie released in 2004. “You would nurture the city by fighting crime.”

After six years of working on a cartoon thief, Sucker Punch wanted to experiment. “We got a little tired of sneaking around and wanted variation, change,” Sucker Punch’s Nate Fox said in an interview with Engagdet. “So, being comic book fans, it made a lot of sense to say, ‘let’s make a super hero game where we get to blow things up’, instead of cautiously looking through a bunch of guards’ patrol paths which, Sly games had a fair amount of that. We wanted to just be brazen and loud and so, that’s where Infamous comes from.”

By 2006, Sucker Punch was officially done with the Sly Cooper series, but it had actually begun work on the superhero game, originally named True Hero, before Sly Cooper 3 released in 2005. The studio had felt it had done all it could with the linear, level-based structure of their stylized series and wanted to move onto something bigger. It wanted to build an open world.

Choosing to pivot to a big open-world superhero adventure created technical hurdles that Sucker Punch had never dealt with before. The studio had to develop new tools and a new engine to create a city in which the player could move in any direction without breaks in the action, a far cry from the load screens and segmented levels of its previous work. But Sucker Punch wanted to keep a core part of what made its games punchy—and in particular it didn’t want to lose the stylized, colorful, and cartoony art style that had made Sly Cooper and Rocket stand out.

The early version of Infamous that Zimmerman described was an open-world mix of Nintendo’s village life simulator Animal Crossing and Sucker Punch’s take on The Incredibles, complete with a beautifully bright visual direction that looked nothing like the more grounded style of Infamous and its sequels. Cole, who didn’t even have the name Cole yet, was still human, but he was animated with a Sly Cooper–style bounce to his walk.

Credit: Sony

Players would create their own superhero persona by picking between different powers, switch between civilian clothing and a supersuit, open new shops and locations to keep citizens happy, and fight crime in order to maintain the city. There was to be a small amount of cosmetic customization with the player character’s outfit and hair, as well.

Sucker Punch iterated a number of new powers that didn’t make it into the final game (though some eventually made their way into Infamous 2). One such power was telekinesis, which would let the player stop metal objects and use them as throwable weapons. Former Sucker Punch developers told me the studio built different prototypes for a number of different powers, but many of them didn’t get fleshed out to the level of the abilities in the final release.

A “clean and dirty” system, which remained in the final game in a smaller way, was a prominent part of this early concept. The worse the player did during missions, the more the city would resemble real-world New York City. The better you did the cleaner things got.

This system is one of the more obvious parallels to Nintendo’s lighthearted life sim. In Animal Crossing, the player character has to pick weeds, remove trash, develop the downtown areas, fill out the museum with fossils, fish, and bugs, and complete fetch quests in order to keep villagers happy. Animal Crossing: New Leaf, which launched in 2014 on the Nintendo 3DS, took this concept even further by giving players a town rating based on their actions. The happiness of each individual animal you cross is of the utmost importance.

Another defining aspect of the early Infamous concept was its reliance on fetch quests, in which the earlier version of Cole (nicknamed Gearwolf by developers), would complete tasks for citizens. The combat Infamous is known for still played a prominent role, as well, but the main character didn’t get his powers after a strange bomb leveled six blocks of Empire City, like Cole does in the final version of Infamous.

At one point, NPC characters in Infamous spoke in gibberish and emotes when Cole approached them on the street—perhaps a similar approach to Animal Crossing’s Animalese dialect of gibberish.

So why did Sucker Punch shift away from this concept and toward the version Infamous that ultimately saw release? None of the sources EGM spoke to could provide direct insight into the decision-making process, but the timing of a new console generation and the studio’s relationship with Sony may have played a factor. Some time after Sucker Punch made the decision to create a sandbox superhero game, Sony asked first- and second-party studios to take their projects in a more serious direction in order to compete with Microsoft’s lineup. That’s part of the reason why Naughty Dog moved on from primary development on Jak and Daxter and onto Uncharted.

Credit: Sucker Punch, Sony

Whatever the reasoning, this shift led to integral members, mostly artists from across the team, of Sly Cooper’s development leaving Sucker Punch in order to chase projects they were more passionate about. The core team of visionaries, including folks like Zimmerman and Nate Fox, remained.

Many of the developers who spoke to EGM said they loved the superhero meets town simulator idea and were disappointed that it didn’t get to see the light of day. Only a few pieces of that initial design concept made its way to the final version of Empire City and they were a far cry from the vision from their initial creation.

The new direction, for instance, largely invalidated the cleanliness system, as the gritty visuals and catastrophic origin story made cleaning up the city less impactful—although a version of the concept did remain as part of Infamous’s morality system. If players chose to be mostly good, Empire City would be clean and brighter. Choose to be bad and you’d see the opposite. In addition, players could still revitalize some parts of dilapidated neighborhoods, restore clinics to create respawn points. If they chose the righteous path, the city would also be less crime ridden. But none of these systems looked much like the ones Sucker Punch envisioned initially.

While we’ll never to get to play Sucker Punch’s original Animal-Crossing-meets-The–Incredibles version of Infamous, there’s no question these earlier concepts and experiments did pave the way for the final game.

“We are a really iteration-based studio where, you know, this mission that you’re playing isn’t the oldest mission in the game, but it’s probably worked on more than any other mission,” Sucker Punch co-founder Brian Fleming said in an interview after a Infamous hands-on demo at the Game Developers Conference in 2009. “But even then, like the karma, and the powers, and the climbing systems, those are things that, at least for us, really took a lot of integrational polish to start to really interrelate and gel together. We really felt like for a new IP, that was the right strategy for us.”

Header image credit: Infamous, Sucker Punch/Sony; Animal Crossing: New Horizons art, Nintendo; via EGM

Aron Garst is a freelance journalist who covers games and esports for ESPN, Gamasutra, WIRED, Polygon, Kotaku, and plenty of other sites. He has an unhealthy obsession with battle royales and Animal Crossing.