When Jon McKellan was working on the UI for Red Dead Redemption 2 at Rockstar Games, he was part of a team with a seemingly limitless budget. “There’s no concept of the money that’s spent. You know it’s a lot, but that’s all,” he told me.

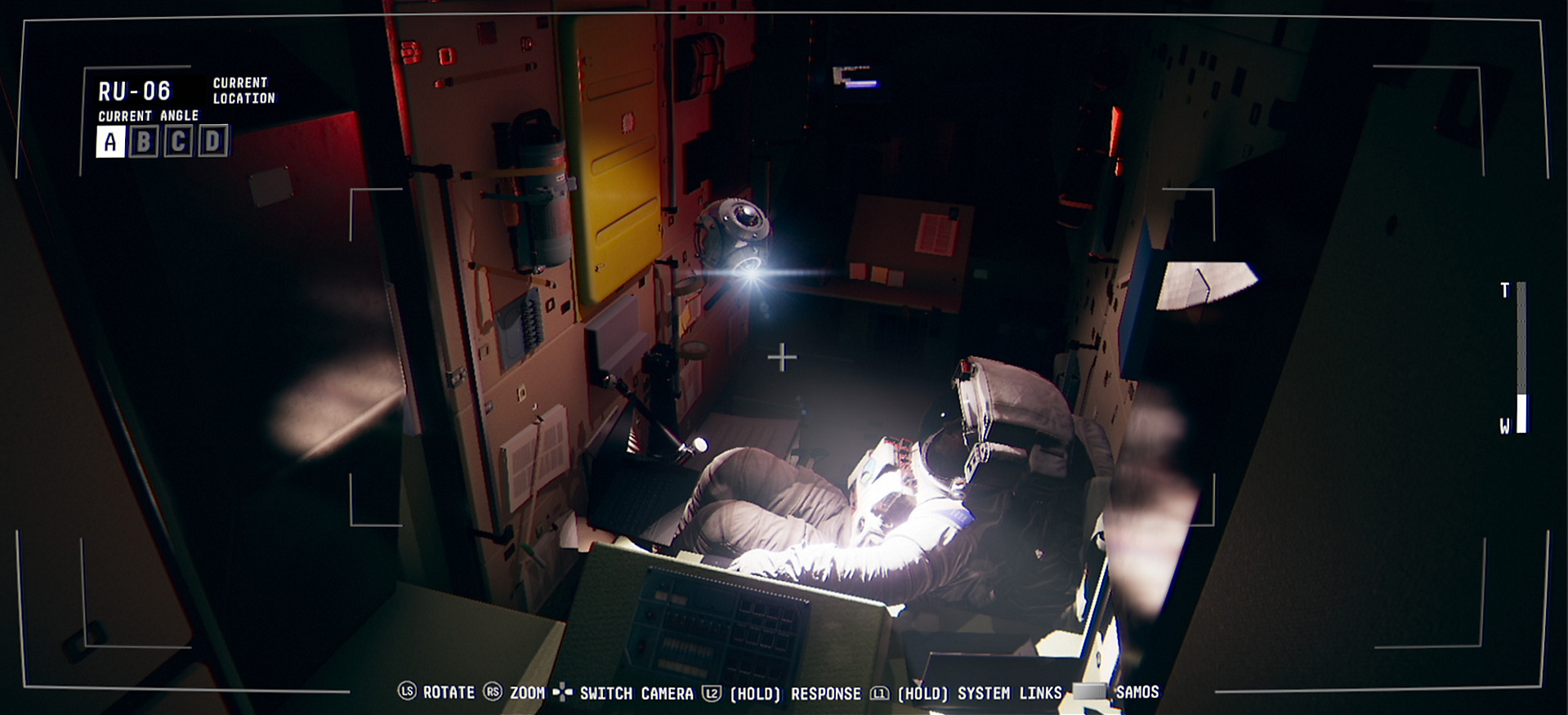

Three years after leaving Rockstar in 2015, he’d founded his own indie studio, No Code, and was finalizing the motion capture for sci-fi thriller Observation. One of the animators would perch on a bar stool, strike a pose in his accelerometer-driven suit, and ask the rest of the team to push him around the office. “It felt very game-jammy, or experimental, but once you put it in place on the model in-game, you’d never know,” McKellan said.

“It was a single percentage of what it would cost to do on a full-suite [motion capture] studio, and it also meant we could recapture quickly. If it didn’t work, Chris [Wilson] put the suit on, went next door, and started doing some movements. It didn’t cost us 20 grand every time we wanted to change a scene.”

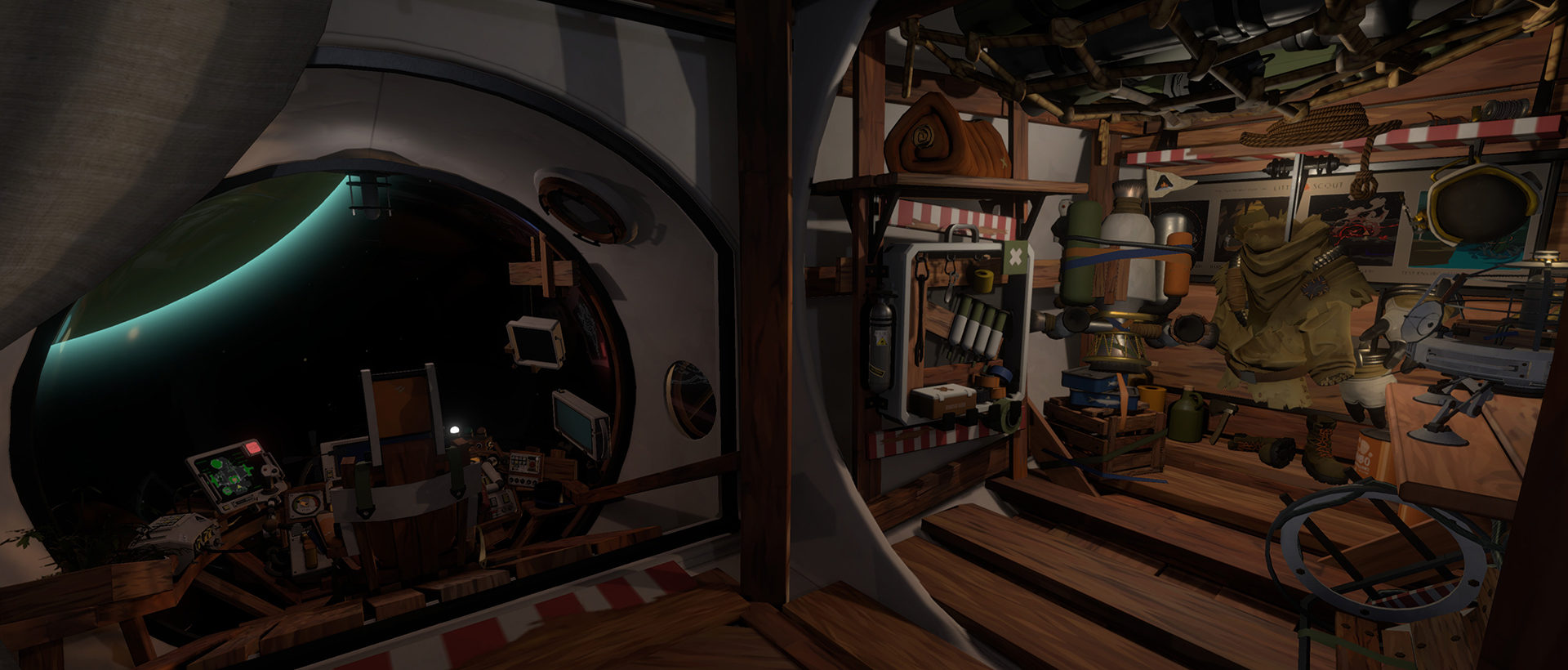

Credit: No Code, Devolver Digital

It’s the type of creativity indie devs must show if they hope to stay within their budgets, which are a fraction of those afforded to triple-A studios. Some of those ideas, like No Code’s homebrew motion capture, are effectively shortcuts: ways of solving a problem without spending as much money as a larger studio would.

Other times, budget-saving measures are baked into the very design of a game. Void Bastards, from Australian studio Blue Manchu, is a stylish sci-fi shooter with levels that are partly procedurally generated. Its sense of randomness and repeatability is essential for its success—but the design also means a team of five developers can create a near-infinite number of levels without building them all by hand.

It’s also clear from speaking to the developers of three of this year’s best-received indie games—Observation, Void Bastards, and the space sandbox Outer Wilds—that being a small studio isn’t just about penny pinching. Indie developers walk a tightrope, balancing budget concerns with the desire to make something unique, something that grabs a player’s attention ahead of triple-A games. “We could’ve made Observation a lot cheaper, but a lot less interesting,” McKellan said.

No Code’s philosophy is to focus the team’s efforts only on the parts of a game players will notice. “I take any given scene and go: ‘If I was to pick one thing out that I wanted to spend the rest of my time on, what would it be?’ That helps you understand what your focus is,” McKellan explained. “I don’t like to use the words ‘corner cutting.’ It always sounds like a bad thing, but it’s often about being sensible with what your game actually needs, what will actually make a difference.”

As an example, he describes a sequence where Emma, Observation’s protagonist, discovers a dead body. “You don’t need to have lots of flickering lights and have smoke everywhere, let’s just focus on her,” he said. “You can go crazy with it, and many triple-A studios do, sometimes to their detriment because you lose focus.” For an argument between Emma and another character, the team pulled the player, who controls an AI aboard a spaceship, away from the action. Your character can’t see the conversation, but they can still hear it.

“We didn’t want the player to sit and watch that, like you would in Alien: Isolation or other games. We thought: ‘We’ll close the door, and now we don’t have five minutes of cutscene animation to make. We can rerecord that dialogue and play around with that entire scene,’” he said. “If it’s not imperative they hear every word… let them do something else away from that scene, and cut the cost dramatically.”

Credit: No Code, Devolver Digital

This approach changes the way the team builds its game worlds, too. For No Code’s The House Abandon, which later formed a quarter of its 2017 debut game Stories Untold, the player is sat behind a single desk in a room, solving puzzles using a monitor and a phone. The room didn’t have walls or a ceiling. “If it’s outside the frame it does not get made,” he said.

“Observation [is] still very controlled environments where we only build what we absolutely need to see, and [outside of that], we don’t touch it.” The team built each room in the spaceship from modular assets that could be flipped or rotated to look different. Each of the ship’s blinking panels looks busy and varied, but in reality they’re all made from the same 15 or 20 assets, repeated in different orders and configurations. The team also built variants of these assets to help tell a story about a given room: one variant was made to look like shiny anodized steel, another to look chipped and worn.

For important rooms, No Code dipped into a budget for “hero items”: specific assets or even whole minigames built solely for that setting. “This room needs a couple of extra things, that room needs a couple of extra things, and then we’d try to work out how many we were spreading around, and how many of them could share some element of functionality or design,” he said.

Initially, the team designed the ship in “graybox”—a development term for literally building the world out of gray boxes—to decide how many objects a room needed, and where they should be placed. This method, combined with building modular assets that could be reused, contributed to a longer pre-production stage than in most games, McKellan said. Clearly, it was worth the time.

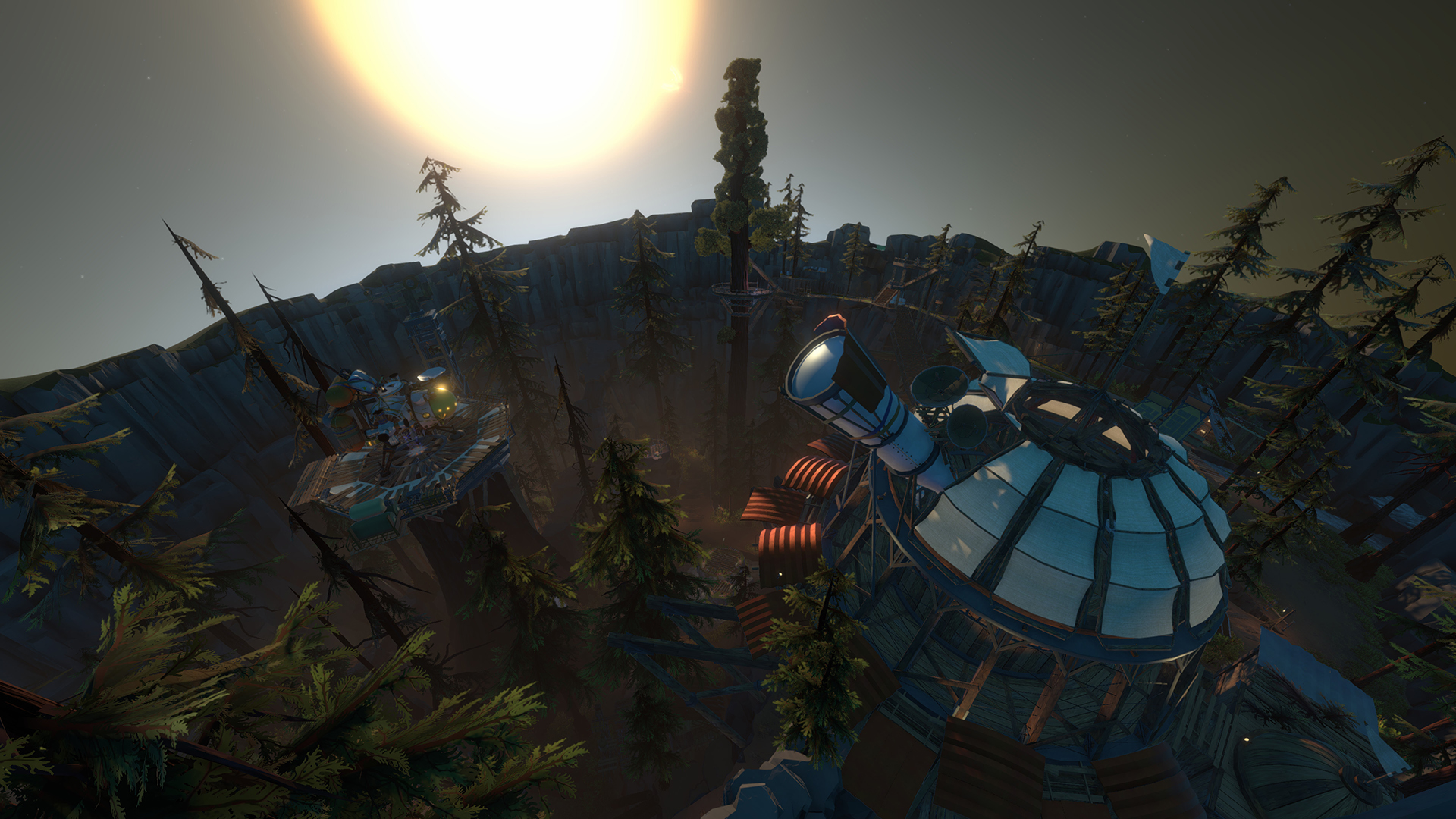

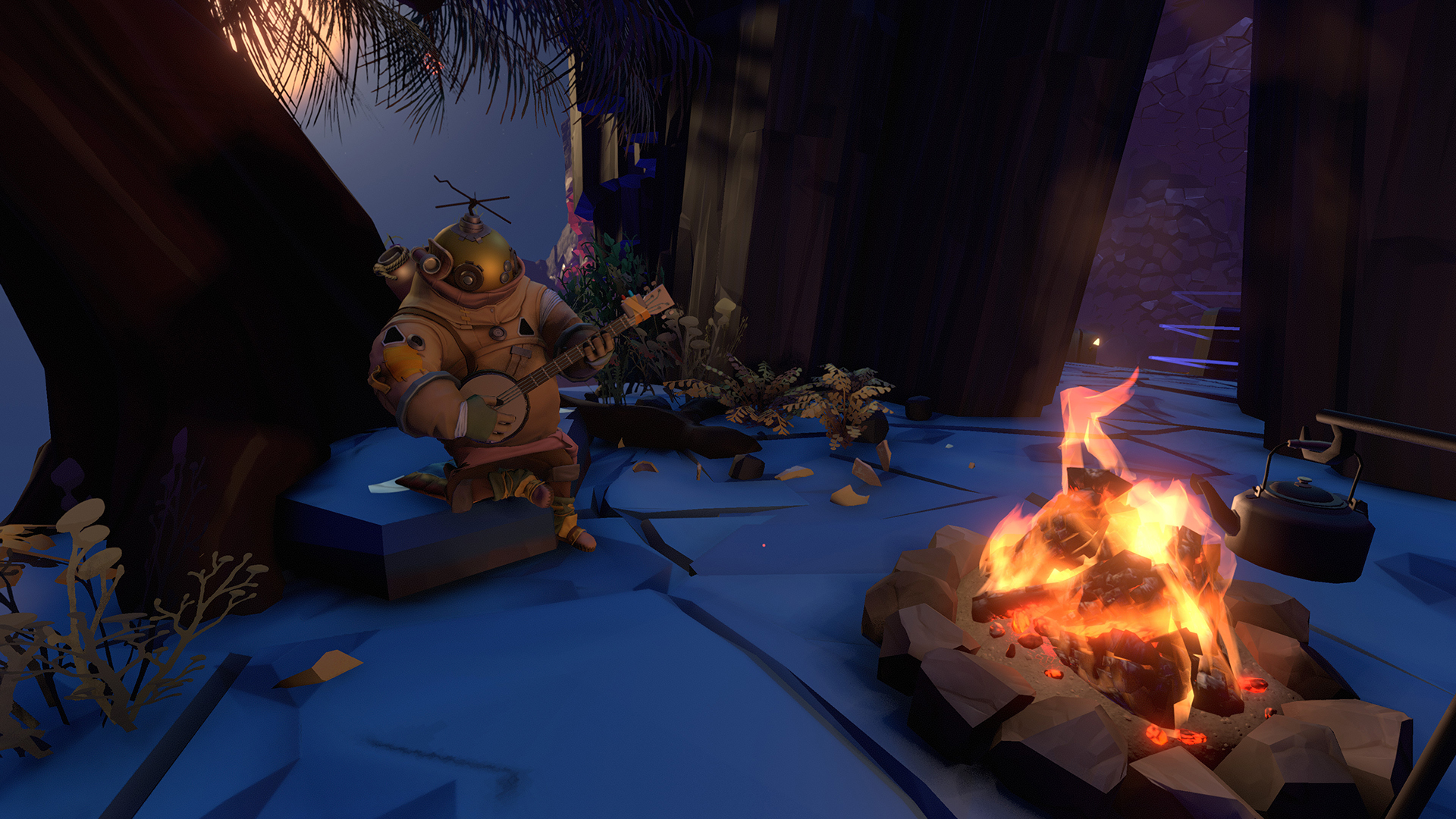

Mobius Digital, the team behind breakout hit Outer Wilds, were of a similar mind: put in the effort up front to save time later. The team built custom development tools early to help the art team place objects on the game’s orbiting planets, for example. Before those tools were made, art director Wesley Martin said he spent an entire week just planting fern trees around the game’s starting area.

“It was so hard to get them in groups, align them to gravity, and place them in interesting ways with the limited toolset we had at the time,” he said. “[After the tools were built] we’re able to do an entire planet’s worth of foliage placement in a day. Rather than waste time, let’s spend a couple of weeks or a month making a tool to both ease the burden on the art team and improve performance on production at the same time.”

Credit: Mobius Digital, Annapurna Interactive

The team also chose an art style—inspired by the iconic WPA National Parks posters of the 1930s and 40s—that was easy to execute across the entire world. The “secret sauce” was hiring staff who were just breaking into the industry, Martin said, not because they were cheaper, but because they “didn’t have preconceived notions that we had to break down, they were onboard really fast. When we tried to work with more experienced people they said, ‘Well, that’s a stupid way to do it.’”

Co-creative lead Loan Verneau said keeping workloads at a reasonable level also cut costs in the long run because it reduced mistakes, which in turn made the bug-fixing stages shorter and simpler. “If everyone has regular hours, they’re not programming while exhausted, or working on geometry while too tired. You save more money, because your tail end doesn’t extend like crazy,” he said.

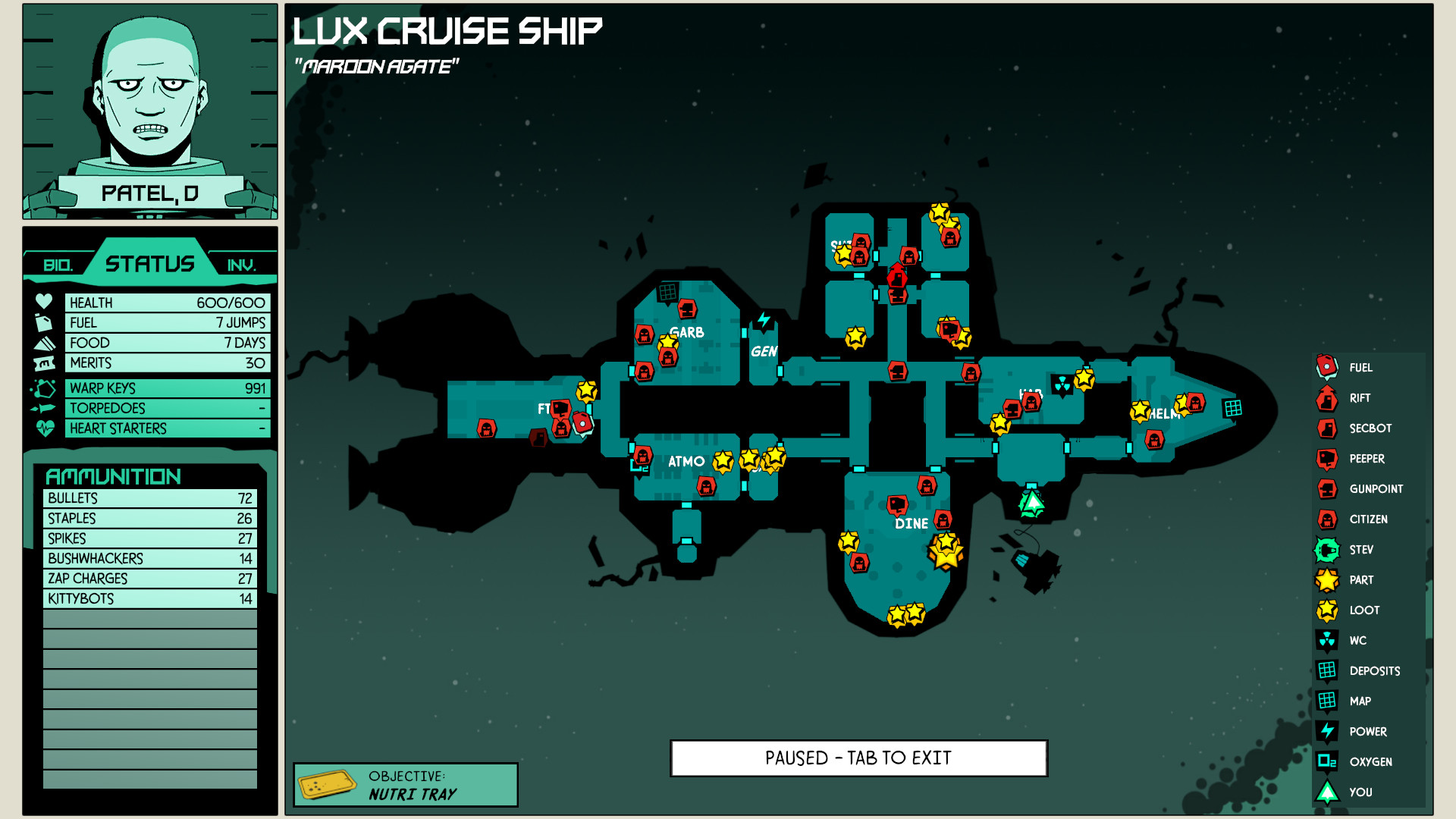

Blue Manchu founder Jonathan Chey, who also co-founded System Shock 2 developer Irrational Games in 1997, has a five-strong team of developers, and the goal with Void Bastards was to create a shooter that would sell in the crowded, triple A-dominated FPS genre. “We were really unsure about whether we could hit that bar,” he admitted.

The “breakthrough moment” wasn’t deciding to use procedural generation to create the game world, but to simplify the art by drawing sprite-based enemies. “A huge part of the budget of modern 3D games is building the skinned mesh characters and animating them.… It’s probably hundreds of thousands of dollars for each character, and that’s our entire budget,” he said.

Credit: Blue Manchu, Humble Bundle

“In old school shooters like Doom or Duke Nukem, the characters were very blocky and low-res, because they just didn’t have the memory to draw them at high-res. [Our art director Ben Lee’s] thought was: what if we do a game with that technology but we draw really high detail textures? Then, we’ll be able to develop them much more cheaply. Without that realization, we probably wouldn’t have taken on the project at all.”

Blue Manchu also saved money by using third-party plug-ins for the Unity engine, such as one for pathfinding, and by accepting imperfection in the game’s code, written by Chey and another programmer. “We don’t try to write really elegant code. We try to bang something out and get it working,” he said. “If it’s no good we throw it away, and if we like it, it gets patched up and fixed, and sometimes it’ll ship as it’s written. It’s very much a philosophy of”—echoing McKellan’s thoughts on Observation—”don’t put effort into something unless it’s really needed.”

Naturally, great games can’t all be built on the cheap, and developers must know where they can afford to spend extra resources. Observation is memorable in part because of its generous design—it constantly gives players new mechanics to play around with, new puzzles to master.

“It’s part of what has made our games fun and unique is that you don’t quite know what’s happening next,” McKellan said. “We’d spend a couple of weeks designing a minigame for the fusion reactor, and it’s looking really good and we have this cool asset, and then you watch someone play and it takes them a minute. It’s the most expensive minute of the game. Our games are weird that way, because the design is very bespoke from one minute to the next.

“We made peace with it, unwillingly. It took a while to realize this is just expensive,” he said. “While you’re in the middle of doing it, you try not to think about that. If you’re constantly thinking about the money and time, you’re just going to get paralyzed.”

Credit: No Code, Devolver Digital

It also helps to spend more money on the start and the end of a game, he said, because those are the bits that matter most to players. “The first and last thing you hear on an album, or see on a film, can dictate how you remember the whole thing. So if you put something really cool at the start, something really cool at the end, people tend to perceive the whole thing that way. It’s not that you’re deliberately trying to make the rest of the game look rubbish, but you have to be aware where to spend that money.”

The Outer Wilds team told me that plenty of their design decisions made the game more expensive, not less. The world is on a time loop, and changes over the course of each of the player’s 22-minute lives. Brittle Hollow, one of the planets, steadily collapses and breaks apart, whether the player is in the area or not.

“One of the jokes we make a lot is that it’s a game you shouldn’t try to make,” said Martin, adding that the studio found a publisher in Annapurna Interactive that wanted the same level of quality as the development team. “Basically everything about it flies in the face of traditional game development.… [Our decisions] increased our production time more than it decreased it.” But ultimately, it’s those decisions that set Outer Wilds apart.

The team wasn’t afraid to cut entire sections of the game, redoing six months of work to ensure they got it right. Fortunately, Annapurna was okay with this approach. “I personally made three different versions of the starting area, and that was six months of my life I’d poured into that place just to gut it and start over multiple times,” Martin said.

“A lot of time, bigger studios run into a problem there. ‘It’s someone’s baby, we invested so much money and resources and personnel into this thing, we can’t cut it because that would be so sad for these people.’ As a small team we were like, ‘Meh, oh well.’”

Credit: Mobius Digital, Annapurna Interactive

The developers I spoke to also stressed the importance of turning limitations into strengths: If possible, they celebrate the areas in which budget restrictions have forced them to be creative. That was how Void Bastard got its vivid art style, for example.

Once the team had decided on sprite enemies—a big money-saver—they kept pushing the idea further and further, Chey told me. What it the game had a comic book art style? What if the team didn’t really texture the world at all? What if they didn’t create real lighting, and just drew shades of light and dark into the wold?

“It’s not proper lighting.… From a realistic, modern, high-fidelity point of view, it’s a really bad solution, but it gives a really strong, unique look to the game. As an indie, it’s better to carve out your own space rather than try to reach the bar other people have established. Once you get onto that kind of idea, you can often get very rich rewards by pushing it further and further.”

The same is true of using a procedurally generated world. For Chey, it wasn’t just about cutting the budget, or being able to make a big game with a smaller team—it was simply inherent to the type of game he wanted to make. “Right now, I only play those kind of games,” he said. “I’m playing Slay the Spire and Dead Cells and Into the Breach, and they’re all procedurally generated, iterative games that you play through multiple times with different parameters. I really love them, and there’s a real growth in the understanding about the way those games should work.”

Void Bastards was an attempt to replicate the combat situations from System Shock 2, Chey said. “The tactical decisions you make, the fact the levels aren’t linear corridors.… It’s really interesting to me, and I don’t think there’s a lot of it in modern FPSes. So, how can we generate an infinite number of these situations so we can really dive into that combat? And procedural generation is the obvious answer.”

Credit: Blue Manchu, Humble Bundle

Rather than generate every level, Blue Manchu hand-crafted 20 to 30 layouts specific to different kinds of ships, and then procedurally generated the placement of hazards, loot, enemies, crawl spaces and locked doors within those templates. “We did think about procedurally generating the level layout, but we thought: There’s a big tech cost for that,” he said. “We can buy out of all that, and maybe it’s actually better for the player that… they can start to learn these layouts. If I go into this ship and I want fuel, this is where I go to.”

Outer Wilds similarly married good design ideas with smart budget decisions. The team decided early on that they’d contrast dense, detailed areas with empty spaces. Martin said it “killed two birds with one stone. It saves on time and resources, but it’s also really important for the design of the game. Timber Hearts village is an incredibly dense place with tons of detail, props everywhere, characters and light all over the place—you get to the surface [of the planet] and there’s barely anything.

“The reason that works well for us is we have this sandbox narrative where you can go everywhere and find things. We wanted to make it obvious to players where you can find information. Creating higher detail places contrasting with lower-detail natural environments created these focal points where players are drawn to. It’s a pretty basic idea that every game does, but a lot of triple-A holds itself to a photorealistic standard where there’s detail everywhere. We chose this stylized National Park poster type of simplification so we could have those varying levels of detail to a really extreme degree.”

Verneau said it also helped the team keep the map uncluttered, and let the player set their own goals. “There’s a lot of open world games where you spend more time looking at your minimap markers than you do looking at the actual screen. We felt like, having content for the sake of adding hours… that was something we were fighting against with this game. Everything you find, you find because it’s curious, not because we put a gold icon there.”

McKellan highlighted the importance of “playing to your strengths” and turning budget constraints into an asset. He spent time examining other sci-fi UIs when making Observation, such as the ultra-detailed holograms in the 2013 film Oblivion. “They’re all very costly and difficult to make, and it’s also not that interesting. What is interesting is something that’s broken, that doesn’t quite work right. So let’s make a UI that doesn’t quite work, and suddenly your limitations are actually your strengths. You’re turning these things that might seem like a negative into a positive, and it has a huge impact.”

Credit: Mobius Digital, Annapurna Interactive

McKellan said indie developers are no more creative than many in triple-A—but they’re forced to come up with more creative solutions to problems. As smaller, more agile companies, they’re also able to learn and adapt faster, and all four developers said they’ll take lessons from their most recent games into their next ones.

One of the lessons that McKellan learned was the need to focus on localization earlier. Observation was translated into 11 languages, and most of that work occurred in the last four months. It was a “complete nightmare” and drew his focus away from other parts of the game that could’ve been improved. “If we can do that stuff well, there will be more time for the creativity, more time to polish.” Chey said that, for his next game, he’d like to run a more extensive beta phase to gather data from players, emulating Slay the Spire’s extended testing period.

Martin and Verneau want to concentrate even harder on preproduction, front-loading money into the tools they make and the staff they hire early, leading to savings down the line. “For most of the game we made the entire art of it twice, for some places three or four times,” said Martin. “That was a lot of iteration we could’ve cut down with more preproduction.”

Verneau acknowledges that spending money upfront is a “leap of faith.” But, in a way, so is the entirety of indie development. Every project is a risk, and there’s no promise of rewards at the end.

“You might spend four years of your life and it gets some stupid meme and everybody hates it for no reason,” said Martin. “There’s just a huge risk involved with development and you just have to sit comfortably with that, especially in indie.”

Header image: Blue Manchu, Humble Bundle

Samuel is a freelance journalist. When he first played TF2, he couldn’t work out how to fire his gun—until he read a troubleshooting guide. You can find him on Twitter @SamuelHorti.