Everyone remembers the first time they hopped off a train in an unfamiliar town, greeted the strange locals, scrounged in the dump, and got strong-armed into a home loan and a convenience store job by the only guy in town who seemed to offer these opportunities. Starting out in Animal Crossing has gotten friendlier with each successive entry, and in the process the proliferation of options and responsibilities given to the player have changed their relationship to the town, or, in the most recent entry, an entire deserted island. Over the course of the main entries of the series moving from GameCube, to DS and 3DS, and now to the Nintendo Switch, Animal Crossing has taken on features similar to city building and simulation titles, importing the ideas about communities and governance these games represent. These games have tended to present communities as systems to be optimized through careful planning and subtle behavioral nudges. While it’s true these choices can have significant consequences, these games tend to focus on the idealized, positive outcomes, excluding some very real negatives in the process.

In Animal Crossing: New Leaf for the Nintendo 3DS, the civic quality of your responsibilities becomes explicit, as the first player to move into town is named Mayor. Alongside your secretary Isabelle, you can set town ordinances which shape villager behavior, decide on additional features for your town and collect funding for them through public works, and even intervene if one of the villagers has inherited an objectionable catchphrase from another visitor or town. However, your office as mayor, and what is under your control from that position, is generally separate from the ongoing capitalist expansion of Nook’s store and real estate empire.

The lines have begun to blur in Animal Crossing: New Horizons, however. The final Nintendo Direct before the Switch game’s release revealed that not only have the player’s abilities to change the features of the island and control the comings and goings of villagers drastically expanded, but also that newly minted CEO Mr. Nook now has a seat alongside Isabelle’s in the town hall, as well as piloting an incentive program, monitored by smartphone, to increase community harmony.

I was surprised at how deliberate the vocabulary used to describe these changes was in that Direct. The island is presented as an empty backdrop to be acted upon, and the player can now don a hard hat to dig new rivers and ramps and even alter cliff faces, all elements of the environment which were unchangeable in previous titles. Further, animal villagers are now invited to the island and assigned to various demarcated lots, a passport item indicates surveillance of your comings and goings, and CEO Nook’s Nook Miles app gives you a constant to-do list of productive tasks to complete. These features were introduced alongside the language of productivity and expansion—terms like “services” and “development” resulting in, ultimately, a “perfectly planned community.”

Credit: Nintendo

While it doesn’t put the player in the perspective of managing a complete simulation of resources and populations, New Horizons’ new perspective does force you to think a bit more like a city planner, one of the stated goals of another well-known series: SimCity. In an essay about the political and theoretical influences of city builders, Kevin Baker notes that Will Wright was inspired by Jay Wright Forrester’s Urban Dynamics when developing the first SimCity. The book espouses “hands-off” policies, focusing on business initiatives over direct provisions like providing affordable housing or assistance to homeless people, and so the game ends up endorsing a perspective of “if you build it, they will come”—that if you simply zone and lay out a city correctly, (starting, in the case of SimCity, with a completely empty plot of land), economic growth and citizen satisfaction will follow. This idea, whether applied to designing small communities, cities, or running an entire country’s economy, positions itself as non-interventionist, passively shaping or catering to specific behaviors.

But these supposedly invisible forces can aggressively shape our behavior, or rather the scope of behaviors we are given to choose from. Instead of resulting in a sort of set-it-and-forget-it, optimized society, these plans often backfire. In many cases, it leads to runaway gentrification, precarious employment, and growing homelessness in cities that prioritize attracting business over a more holistic view. Beyond local and national governments, major tech corporations have also looked at getting into the game of altering and optimizing cityscapes, with similarly dysfunctional outcomes.

Tech companies see cities as systems to apply their innovations to, such as app-based services like Uber and Deliveroo, which fundamentally change existing industries and jobs, or Google and Amazon’s larger Sidewalk Labs and HQ2 projects. The idea that catering to these developments will bring economic growth to an area encourages local governments to compete to provide inviting contexts for Amazon or Google to build their experimental data extraction infrastructure alongside commercial and surveillance initiatives. The promise of these initiatives has its basis in the idea of a city seen as a simulation—that with the right technological enhancements and adjustments to residents’ behavior (often determined by large scale collection and surveillance of data), it can be set on a path to optimum economic growth and efficiency. As the comparisons between the promise and realization of Google’s smart city projects demonstrates, these sort of optimization strategies rarely live up to the hype, and often produce new frustrations for city dwellers, but they do handily allow for both the maximum power and minimum responsibility for the government and private enterprises at the top.

Credit: Electronic Arts

Many of the largest issues of our time are significantly determined by how urban, rural, and suburban areas have been laid out and managed under this philosophy. The major drawbacks of near-universal car culture, the inequality long baked into where you will be able to buy or rent housing, and what resources likewise become available to you, the waste produced by these ways of life and where to put it, and the increased atomization of work and home life are also all mostly abstracted out of simulation games. While the consequences of these planning approaches become obvious in life, they play out very differently in the scenarios presented by SimCity and, similarly, Animal Crossing: New Horizons. In both cases, the game naturalizes the assumption that these systems work, because video games are self-contained and self-justifying simulations.

Games like SimCity have been promoted by proponents in the gaming and tech industries as a useful tool for teaching the fundamentals of city planning, and Animal Crossing: New Horizons has taken some cues from the same philosophies in terms of how it frames the process of developing an island, but their visions of a functioning community leave a lot out. You start on an empty plot of land or deserted island, from which resources consistently spring forth, owned or relied on by no one else. There’s no dump, no parking lots, and the citizens are either abstracted data points or cartoon animals. There’s not a question of what happens to the animals you don’t invite to live on your island, or the people who are priced out of living in your thriving SimCity. And of course, there’s no nefarious purpose to the data CEO Nook collects through the app or the consolidation of services he provides. All of these features only manifest within the games as a net good for community cohesion and vitality, which just has to be calibrated properly.

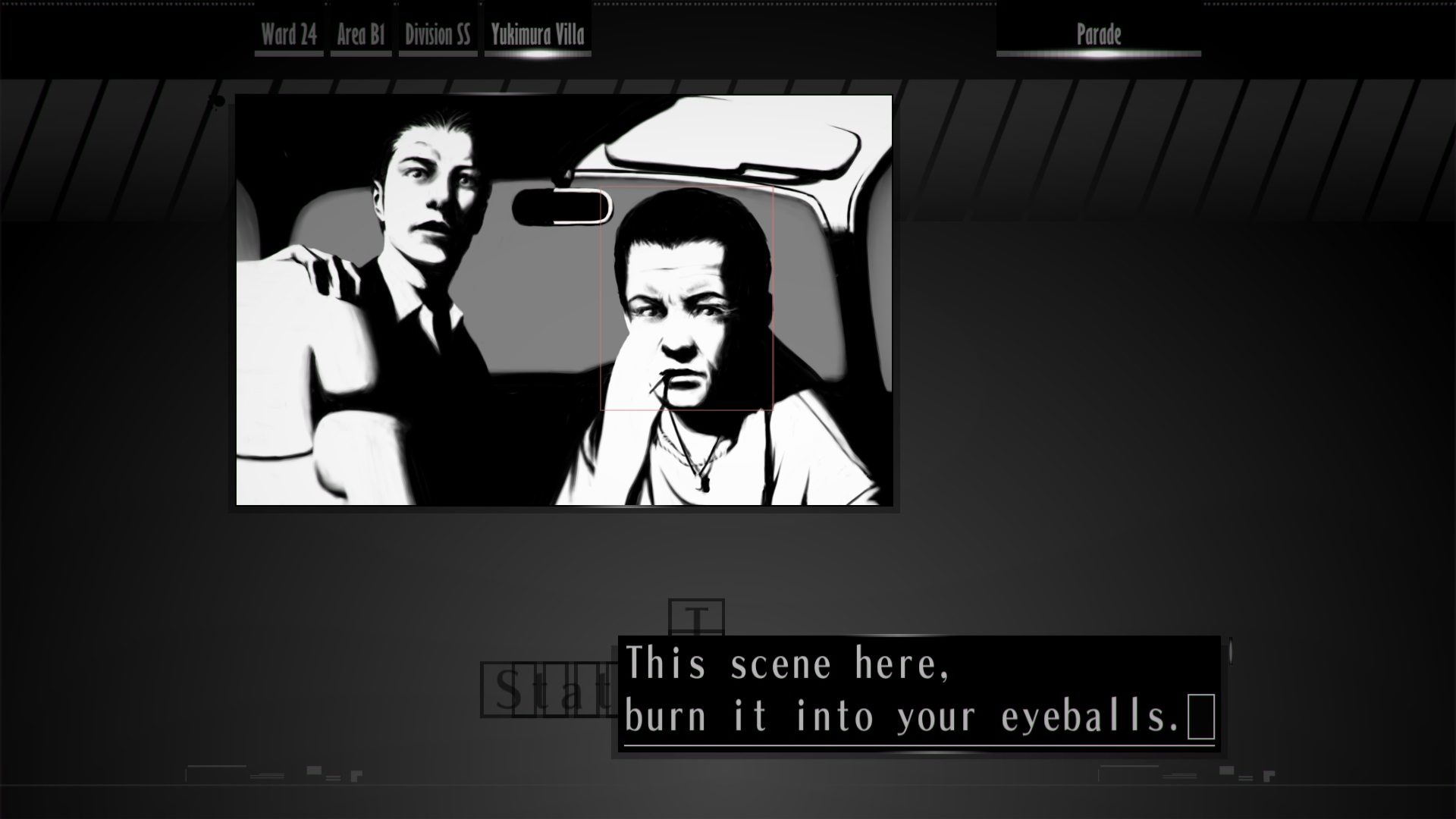

Almost counterintuitively, some comparatively linear narrative games are able to more effectively communicate problems that arise in communities of any scale. The 1999 PlayStation visual novel The Silver Case, remastered in 2016 for PC, doesn’t offer the player any way to significantly change the outcome of the plot or the shape of the city it takes place in. However, it offers a complex narrative of a city where traditional political institutions have lost their power, and instead a variety of nongovernmental organizations representing tech, communications, real estate, and law enforcement largely control the city. Citizens of the Ward 24 area are specifically selected to live there and are constantly monitored by a variety of mysterious surveillance technologies. Further, the game notes that the wealth gap within the city is exacerbated by an information gap—the wealthy and powerful remain so simply because they know much more about how these systems work.

Credit: Grasshopper Manufacture Inc.

Both real life and fantastical consequences of such extreme city planning and social control emerge over the course of the game. One of your co-workers is shaped by his experiences growing up in a small town that was abandoned to cover up an ecological disaster caused by a polluting corporation. Murders and other crimes are committed by a number of individuals raised in government facilities and “seeded” into the general population, who can be controlled at will to act in the various organizations’ interests. In every case, these conspiracies of power and control have a cannibalistic character to them, in that those at the top sacrifice or consume the ward’s population to maintain their monopoly over the city’s development and information networks.

On a smaller scale, the recently released Act V of Kentucky Route Zero allows the player to explore an ex–company town, previously a community of miners controlled by the Consolidated Power Company, in the immediate aftermath of a flood. The scene dredges up the ghosts of the past and presents a layered history—of the people who inhabited the land before it was a company town, of the general store where you could only spend company scrip, of how the store was transformed into a café by the community who stayed after the power company abandoned the area over the process of deindustrialization. Every corner of the town is full of these stories, which provide a sort of open-ended hope about how those who remain will shape the town’s future in the face of a tragedy.

Rather than just presenting a fantasy of social control and optimization, video games can also interrogate our assumptions about how to build and manage community, and draw attention to how the convenient abstractions that we use to evaluate and plan cities can deform our perspective. While games that focus on narratives about life in these cities and communities can draw attention to these issues, simulation-oriented games like Animal Crossing and SimCity often shy away from digging into them. Of course, I love designing new outfits, finding a just-right piece of furniture, or catching a new type of fish for the museum. I just wish I had the choice to opt out when a certain furry real estate mogul pitched me his new smartphone app.

Header image: Nintendo

Emilie Reed is a writer and curator based in Glasgow. Her work focuses on the history of videogames, their presence in art museums and galleries, and expressive forms of production within videogames. Her writing has previously appeared in The Arcade Review, Critical Distance and Rock Paper Shotgun.