Two things stick out after playing Alan Wake again for the first time in 11 years: This game is better than I remember, and Alan Wake is more of a dick than I remember.

Back in 2010, I was also a writer. Technically, I still am a writer, but I was obsessed with becoming a serious writer. I was even going to school for it. I was getting a Master’s so I could call myself a Master writer.

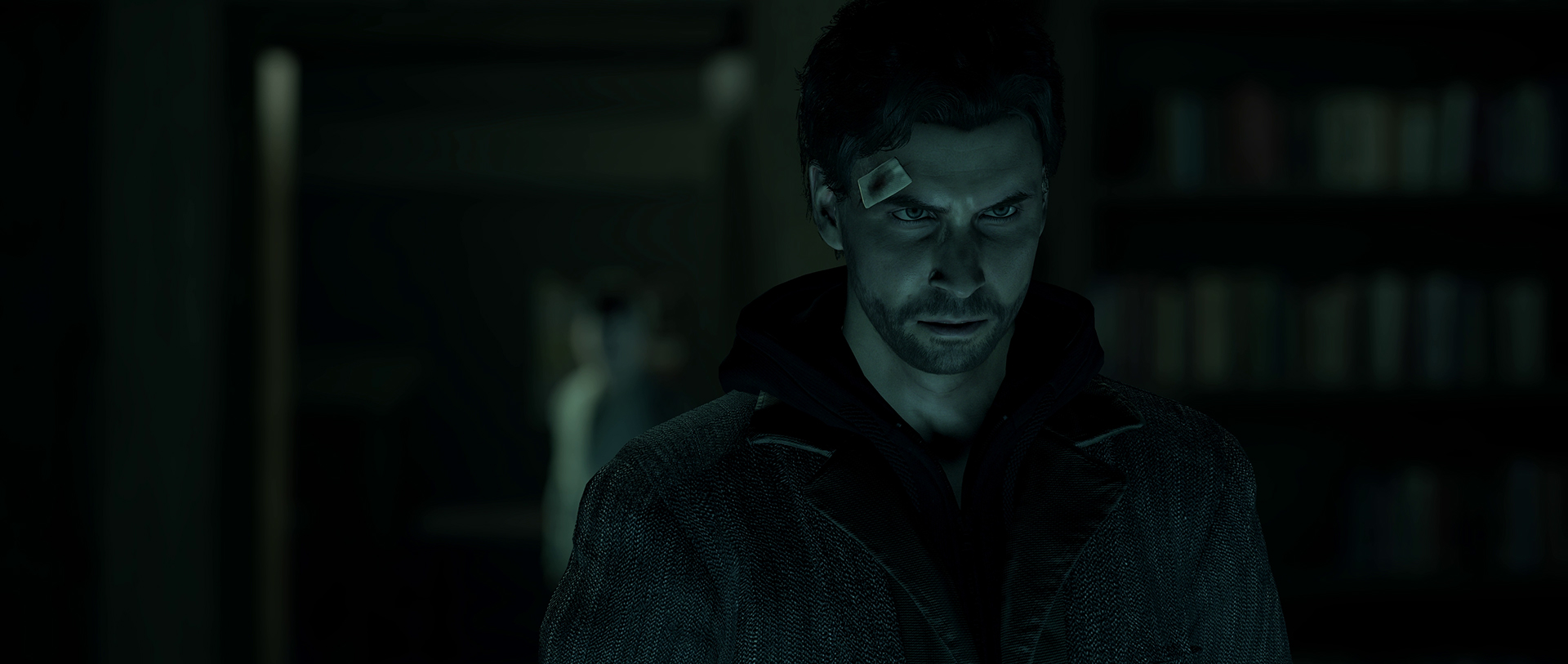

Alan Wake is likewise a serious writer. He’s dark. He’s brooding. He’s also a best-seller. He lives in a big New York City apartment with his beautiful, doting wife, Alice. When he goes on a book tour to promote another best-selling novel in his Alex Casey mystery series, he’s so miserable that he drinks himself into a stupor to numb the pain. When he faces paralyzing writer’s block, he whisks Alice away to a cabin in Bright Falls in the middle of nowhere, and takes his frustrations out on everyone around him.

Alan Wake is a serious writer, and we all know that serious writers can never be happy.

The first time I played Alan Wake, in 2010, I sympathized with the titular hero. I laughed when he slagged off the kindly old radio host who wanted to interview him. I rolled my eyes along with him when he met Rose, a waitress at the local diner who was his number one fan. I cheered when he punched Dr. Emil Hartman in the face for even suggesting that he needs help. I even thought, as far as video game characters go, his outfit was cool.

Let me reiterate that: I thought Alan Wake’s outfit was cool.

I’ve learned a lot in the last 11 years, namely that if you’re struggling with your creative output to the point that it’s impacting the rest of your life, then you should either go to therapy or simply put whatever you’re working on away for a while. But I’ve also learned that the myth of the “serious writer” and what behavior as a “serious writer” is acceptable is just that: a myth. Playing Alan Wake Remastered, when Special Agent Nightingale mockingly calls Wake “Raymond Chandler” or “Ernest Hemingway” or “Stephen King,” I completely sympathize. To most people, those don’t sound like insults. But to anyone who has ever dealt with someone suffering from Serious Writer Complex, Nightingale’s obvious disdain for writers makes perfect sense.

Part of the joy of playing Alan Wake Remastered is getting to experience the game again with an older, marginally wiser mindset. For what it’s worth, I don’t think creative director Sam Lake and the rest of the team at Remedy Entertainment that originally created Alan Wake are complete fans of the guy. (I can’t be 100 percent certain about this, but I even suspect that Lake uses Wake as a sort of apology letter to anyone he’s been a dick to on his road to creating his own art.) They take every opportunity they can to show Wake being a complete jerk, and the Dark Presence that is the game’s main antagonist is a succinct metaphor for the darkness that Wake brings into his own life. The only way to rid the world of one Dark Presence is to rid it of another. Wake up, Alan Wake. Say hello to your life.

Of course, there are complications to this reading. Remedy getting back the rights to Alan Wake from Microsoft means that the Finnish studio can now return to the world in whatever way it wants to, and it’s done so twice so far—most recently in Alan Wake Remastered, and previously in the “AWE” expansion to Control. It’s the latter output that throws a stick in the spokes of this reading of Alan Wake, that the character is flawed, unhealthy, toxic. The character of Dr. Hartman always represented a sort of tyrannical, untrustworthy view of mental healthcare, as he tried to use his creative patients to evoke the Dark Presence living in Cauldron Lake. “AWE” takes this a step further, completely strips Hartman of his humanity, and turns him into a disfigured monster, possessed by the Dark Presence and Hiss, hellbent on destruction. To make matters worse, it’s the ever-dutiful Alice that wanted to bring Alan to Hartman in the first place.

Part of what is interesting about revisiting the character of Alan Wake in Alan Wake Remastered is to trace the trajectory of Remedy’s protagonists. Max Payne is an obvious homage to the hard-boiled detective, but he’s also more self-aware than Wake, more honest in his purpose of blood-soaked revenge. (Rockstar had to go and undo all of that in its ill-advised Max Payne 3, but that’s for another time.) Quantum Break’s storytelling approach meant that players got to experience the story from both Jack and Paul’s perspectives—the latter representing megalomaniacal pursuit of technological revolution, the former representing the stifling force of conservatism. Control’s Jesse Faden is a culmination of all of Remedy’s efforts: She’s an outsider with every right to be hateful and skeptical, but instead decides to use her abilities to help her adopted family of the Bureau while not completely adhering to its traditions.

In many ways, Alan Wake represents a turning point for Remedy. While Max Payne was an original character, Alan Wake is much less reliant on tropes. He’s psychologically richer than his predecessor, and the story is much more willing to take risks. But it’s also in the gameplay that Alan Wake proved to be a turning point, showing that Remedy didn’t need to rely on high-flying, bullet-time antics to make its action tense and satisfying.

The two-step process of taking down enemies in Alan Wake is, I think, underappreciated. Having to “break” an enemy with light before you can kill them means that you constantly have to juggle between your flashlight and your gun. On top of that, the way that enemies are constantly charging towards you with hatchets and sledgehammers and chainsaws while screaming at you in garbled, glitchy voices makes the action feel horrific. These aren’t mobsters or armored goons shooting at you from a distance; these are shadowy woodsmen emerging from the dark, between the trees, to slaughter you in cold blood. For all its obvious references to the original run of Twin Peaks, Remedy seemingly predicted the introduction of the disturbing woodsmen from The Return, which would come out seven years after Alan Wake.

In all the ways that it needs to, the Remastered version of Alan Wake—handled with a great reverence and respect for its source material by d3t Ltd.—enhances the original. Considering the engineers at d3t not only had to translate the game across two console generations, but they also had to bring it to a completely new architecture in the form of PlayStation consoles. This, alone, is no small feat, but considering I played it on an Xbox Series X, I can’t speak to how well the game translated to PlayStation 5.

What I can say is that d3t preserved the most important aspect of Alan Wake, and that’s its atmosphere. Bright Falls’ dense and twisting forests are as imposing as ever, and a big part of that is how d3t introduced volumetric lighting to every square inch of the game, not just in the streetlight checkpoints. The way the moonlight hits the fog and Alan’s flashlight bounces off the environment highlights and enhances the original’s artistic direction without trying to wrongfully “improve” upon it the way that other remasters can.

The characters, too, are simply more “enhanced” versions of their previous selves. In some ways, this really works—the stitching in Alan’s tweed jacket is particularly impressive. Other times, however, d3t’s slavish devotion to Remedy’s original vision can mean you have characters that appear stiff and unreal, most noticeably in Alice. The overall effect is something that’s stuck halfway between the past and the present; fans who know the definition of “remaster” will not be bothered, but new players with more contemporary expectations might find the slightly weird faces and 2010 animations somewhat distracting. Still, the consistent 60 frames per second during gameplay that I experienced on the Series X more than make up for that.

Really, the only thing that is disappointing about Alan Wake Remastered is that it doesn’t include Alan Wake’s American Nightmare, the game’s more arcade-y semi-sequel. Sure, two DLC chapters in “The Signal” and “The Writer” are included, but the package feels incomplete, both as an historical artifact and as a product, without American Nightmare. I don’t know what kind of technical issues that would have represented for d3t, but I would find it hard to believe that American Nightmare’s architecture was so far off from the original’s that it proved impossible to do. No matter the reason, its exclusion feels a little cheap.

Even without American Nightmare, Alan Wake Remastered represents an artistic and commercial victory lap for Remedy. When it first launched, it performed poorly commercially while gathering a cult following and showing that Remedy was more than just the Max Payne studio. Now, Remedy is a studio that’s truly hitting its stride, with more pots on the burner than ever before and a commercially successful Control to boot. If Alan Wake was the bridge between Max Payne and the more narratively rich games that would come after, Alan Wake Remastered seems like a bridge between Remedy’s roots and its future.

Images: Remedy Entertainment

|

★★★★☆

Alan Wake Remastered does what a good remaster should. It honors the original game’s artistic direction while enhancing it with modern technology, specifically in the form of volumetric lighting. Its lack of American Nightmare as part of the package is disappointing to say the least, but fans of Remedy’s current work would do well to take a trip to Bright Falls, whether they’re returning or visiting for the first time. |

Developer Remedy Entertainment, d3t Ltd. Publisher Epic Games Publishing ESRB M - Mature Release Date 10.04.21 |

| Alan Wake Remastered is available on Xbox Series X/S, PlayStation 5, Xbox One, PlayStation 4, and PC. Primary version played was for Xbox Series X. Product was provided by Epic Games Publishing for the benefit of this coverage. EGM reviews on a scale of one to five stars. | |

Michael Goroff has written and edited for EGM since 2017. You can follow him on Twitter @gogogoroff.