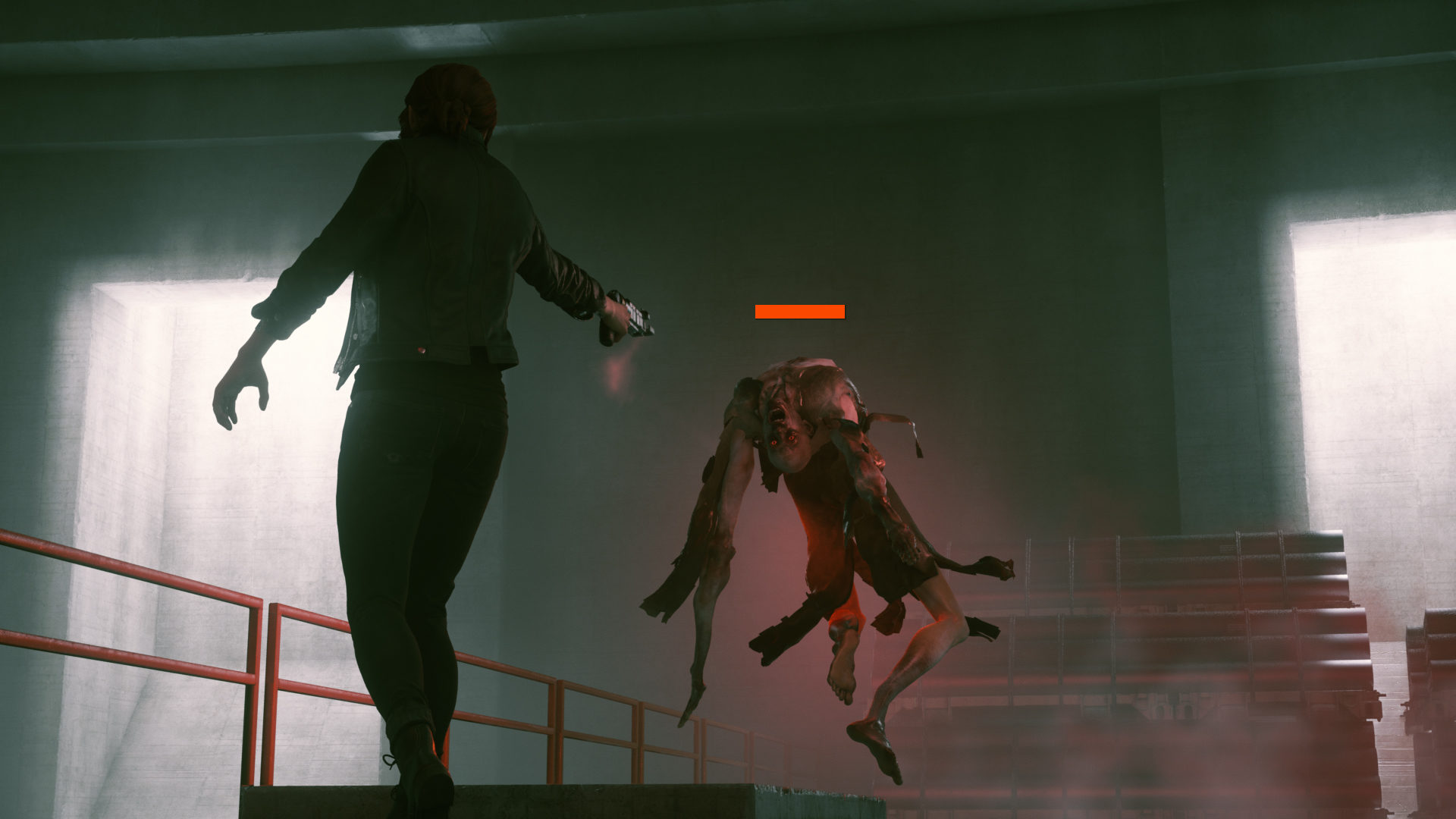

In Control, I burst through the door, wielding my ur-gun in one hand and a fistful of telekinetic bullshit in the other. Down the stairs, a miniature army of goons scatter, taking potshots at me. I put three of them down with precise headshots from my pistol, then fling a garbage can at a fourth. As I reload, one pulls out a rocket launcher and fires, but I pluck his projectile out of the air and redirect it back into his face, taking out a few more in the ensuing blast. On a far-off balcony, two more enemies take aim; I recognize one of them as a deadly sniper, so he takes priority. I hypnotize one of the leftover minions to distract his friends, and then I pry up concrete and detritus from around me, congealing it into a shield as I run for cover underneath the balcony. Finally, I fly up to their vantage point, pick up the lesser goon, and toss him into the sniper. They fall together, a broken bundle of limbs, hissing out of existence as quickly as they entered it.

On paper, Remedy’s Control has all the elements that make up an excellent combat system: satisfying weapons, varied enemies, and a potent blend of supernatural powers that allow you to rip foes apart with ease. (Unlike most shooters, it even offers a number of defensive options besides cowering behind a wall, which, as a fan of more “active” shooters like Dusk and 2016’s Doom, I personally appreciate.) There’s just one problem: By the time I was around two-thirds of the way through the game, I found myself dreading my battles with the game’s orange-tinted antagonists, the Hiss.

To be fair, the constant deluge of foes that Control throws at you definitely contributed to my sense of exhaustion, but that wasn’t the only problem. At that point in the game, I had maxed out all of the abilities that I enjoyed using, and I was drowning in resources and loot because I had completed most of the game’s sidequests, too. There was no mechanical benefit for blasting these enemies; it felt like I was going through the motions simply because the game expected me to.

Credit: Remedy Entertainment, 505 Games

In the cloistered world of video game criticism, the statement that a Popular Game has “too much combat” has become a cliché of sorts. It’s nothing new, of course; over the decades, many observers of the industry have decried the violent, so-called “visceral” gameplay that continues to dominate the sales charts, year after year. From BioShock to The Last of Us, writers have pilloried mainstream video games with literary aspirations as excessively bloody and macho, too focused on crass extremes of human behavior, with stereotypically masculine, even patriarchal themes: war, honor, fatherhood.

While these contentions are largely correct—especially in the triple-A space, where grizzled white male protagonists are still largely the norm, even with games like Control and Gears 5 pushing back—I believe the problem isn’t just the sheer volume of combat, but the monolithic ways that we choose to represent conflict, to represent victory and defeat, in video games. I’m talking, in particular, about the humble health bar.

Credit: 2K Games

The concept of “hit points” goes back to the origins of role-playing games, with the original edition of the tabletop RPG Dungeons & Dragons. In Chainmail, the wargame that served as a forerunner of D&D, there was no concept of health: If a weapon’s attack roll exceeded a soldier’s armor class, they were simply struck dead, and a missed attack would have no effect at all. D&D designers Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax quickly realized that players didn’t enjoy having to invent an entirely new character every time a mook happened to roll high, so they came up with the concept of “hit points” to give even first level losers a shot at survival.

Today, many D&D “Dungeon Masters” (including me) sometimes complain that combat between the players and their enemies can take too long, especially when the outcome is all but assured. In the early days of the game, DMs were encouraged to use frequent “reaction rolls” to determine when a group of foes were likely to surrender or flee, with only the most mindless or fanatical fighting to the death. (In the current edition of the game, this “morale” mechanic is one of many oft-overlooked optional rules offered in the Dungeon Master’s Guide, and it’s rarely invoked at most tables.)

No matter the genre, turn-based or real-time, cartoonish or hyper-realistic, combat in most video games takes basically the same form: bash on the enemies until they’re dead. Of course, the games that prize their battle systems offer varying degrees of tactical depth—say, deploying area-of-effect blast attacks to deal with mobs of small enemies, or stacking debuffs on an elite commander so they don’t slay you in a single blow. While individual efforts vary in their level of sophistication, the overall goal is still the same: Drain the enemy’s glowing health bar, and you’ve won. In most games, once a battle has commenced, there’s no option to de-escalate or parley; you can either choose to strike down your opponent or flee, perhaps hoping that the AI will forget its grudge.

In the past, I’ve written that my favorite moment in the universally beloved The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt came when I finally had the option to talk to the monsters rather than slay them. However, I’m not merely advocating for more games to abandon the concept of violence entirely (though I wouldn’t necessarily be opposed to that). Rather, I feel that games should explore other modalities of combat by using these traditional mechanics to delve into something more complex than bullets tearing through chunks of an HP gauge. Many great RPGs struggle to squeeze nonviolent options into their mechanics because nobody has quite figured out how to make disarming the final boss with a speech check feel more than one-tenth as satisfying as blowing him away with six shotgun blasts. There are many possible ways to solve that problem outside of combat, but we should try to give the player more sophisticated options within the melee itself.

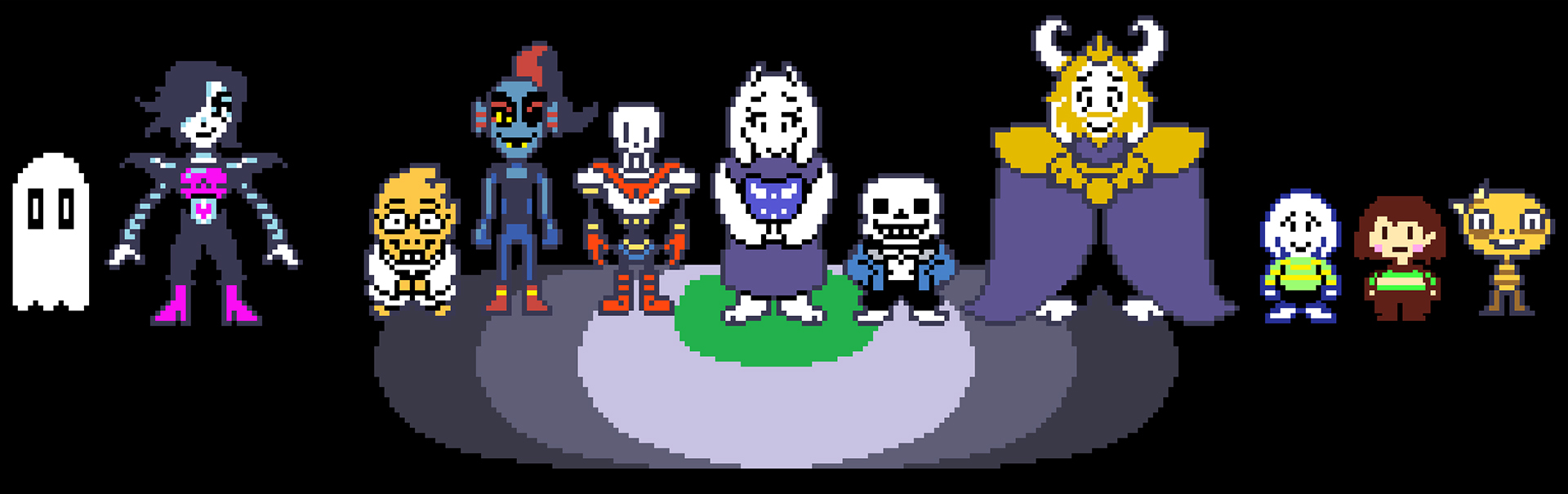

While it might sound a bit strange stated this way, it’s far from a radical idea. Plenty of critically acclaimed games have given players ways of dealing with their foes beyond the obvious, especially in the stealth genre. Levels in the Hitman and Dishonored series are miniature Rube Goldberg machines of death and dismemberment, allowing the player to construct elaborate schemes to eliminate their targets, sometimes even with the victim’s own hubris as the fulcrum. The cult RPG Undertale famously allows you to beat the game without killing a single monster; that game’s vision of pacifism is a tiny heart dodging bullets and lasers like a spaceship in a shoot ‘em up, only one that can never return fire. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater also allows for a pacifist run: Instead of killing each of its fearsome bosses outright, you can drain their stamina with a combination of CQC and tranq darts if you so choose. Even retro games have gotten in on the action. In the throwback Metroidvania Axiom Verge, you eventually acquire a sort of glitch-ray that allows you to devolve your opponents into much less formidable versions of themselves—a robo-scorpion that fires three projectiles is reduced to firing a paltry one—or even convert them into allies.

Credit: Toby Fox

When considering these different approaches to combat, it may be useful to think of them with a concept that only usually applies to the world of board games: multiple win conditions. (For example, in the asymmetric card game Netrunner, either player can win by raking up enough “Agenda” points, but the corporation player can also attempt to kill their vulnerable hacker opponent with damage-dealing cards.) Of the most popular games of the past few years, FromSoftware’s Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, offers one of the most intriguing incarnations of this sort of design in the form of its “posture” bar. Instead of just chipping away at an opponent’s HP, your spritely shinobi can deflect an opponent’s attacks with perfect timing, which slowly builds up a meter that rapidly decays if you let up on your slices. Fill the meter to the top, and you can hit a devastating Deathblow, which is mechanically identical to draining an entire segment of their health bar. Since the posture meter builds faster as they lose HP, the game encourages you to land clean strikes early on, then build the pressure as the fight progresses. It’s no wonder that other triple-A games like Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order have already taken a similar approach.

When I sit down to run a session of my favorite tabletop RPGs, I always like to think in terms of the obstacles I can place in my players’ way. I can try to spread rumors to ruin their reputations, kidnap or otherwise jeopardize NPCs that are important to them, drive them insane with mind-bending interlopers from other dimensions, or take a sledgehammer to the fragile institutions they’ve managed to build with their hard-earned loot. Disco Elysium has two HP pools, your physical Health, and your mental Morale, but perhaps we need even more than that. In a good session of a game like D&D, I feel the full breadth of the human experience in the same way that I do when I read a good book or binge-watch a solid season of TV. When I play most video games, I have a good time, but I don’t feel that range of conflict. Instead, I mostly think about following the same combat flowchart for 95 percent of the game and repeating it ad infinitum. I’m confident that it’s within our power to change that for the better.

Steven T. Wright is a reporter and novelist living in the Twin Cities. He is the former independent games columnist for Variety, and he has written for Rolling Stone, Polygon, Vice, and many others. He almost named his novel after a city in Final Fantasy, but his friends talked him out of it.