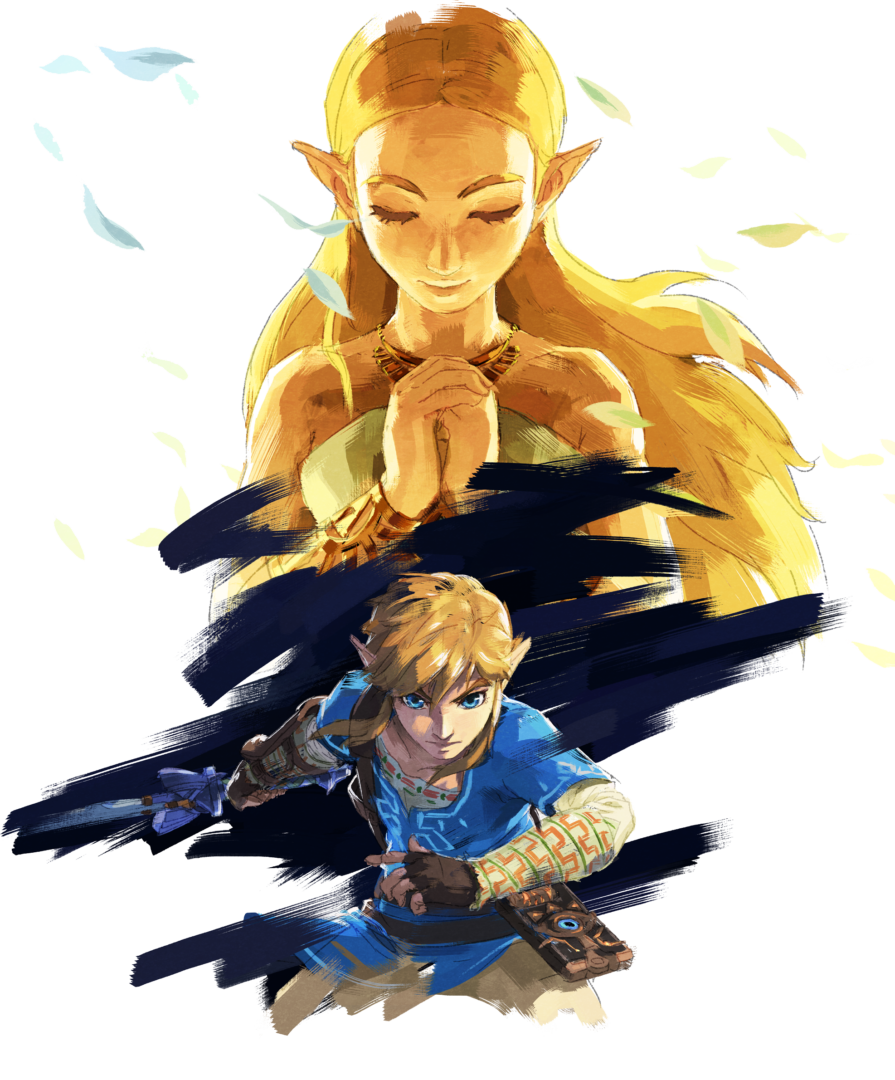

The first time we see Zelda in Nintendo’s E3 2019 teaser trailer for the Breath of the Wild sequel, she’s standing in front of a torch-bearing Link, staring down an otherworldly hand clasped around the dried husk of (we presume) Ganondorf’s body. Zelda is dressed in similar fashion to our voiceless hero, and she has noticeably changed since last we saw her. Her hair has been cut in a short bob and she’s boldly leading the way as an active part of what looks like an underground excursion. The days of Zelda being withheld in a tower for 100 years has passed. This is the dawning of a new age.

But just as suddenly, we’re given a series of scenes out of sequence in which we’re lead to believe something happens to Link—the ground caves way beneath Zelda, Link reaches for her, and his hand starts to glow, just as we see Zelda pivot and stare down Ganondorf’s reanimated corpse. In the end, Hyrule Castle breaks away and floats into the sky, leaving us wondering what might have happened to our heroic duo and whether they’re once again separated or finally bound together in this latest installment.

The sequel was an unexpected announcement that reawakened an old, battle-worn cry to play as the famed princess of legend—a call that goes back to the earliest trailers of its direct predecessor. When the first Breath of the Wild trailer dropped in 2014, we were introduced to an androgynous character with bright blue eyes in a blue tunic wielding a bow. The hallmarks of our hero Link—the typical green tunic and Master Sword—were nowhere to be seen, leading audiences to believe perhaps it wasn’t Link at all. At best, fans thought it might be Zelda in the trailer vaulting off a horse to take down a robotic Guardian. At the least, they mused on the possibility of playing as a female Link.

Those beliefs were further supported when longtime Legend of Zelda series producer Eiji Aonuma said during an interview with VentureBeat, “No one explicitly said that that was Link.”

Cue two years of speculation, memes and viral online discussions analyzing the lore behind the Legend of Zelda series. Zelda and Link are intertwined with one another as beloved reincarnations of a goddess and the hero destined to save her. Although it would have been the first game in the series that allowed the player to control a gender-swapped Link or the lead female character herself, it wasn’t completely out of the realm of possibility. There was nothing in the lore of the series that precluded those things from happening.

But in 2016, during an interview with GameSpot, Aonuma walked back his earlier comments and shut down any speculation over the character. He announced that it was Link in the trailer, but that his team had at one point considered making Zelda the lead character. That idea was ultimately rejected because it changed the dynamic of the characters’ relationship.

“If we have princess Zelda as the main character who fights, then what is Link going to do?” he asked, hinting that Link’s own identity would be at risk, that he would be nothing without a princess to save.

In another interview with Kotaku, Aonuma further explained that the Triforce is split between Link, Zelda and Ganon, the all-powerful king of darkness and arch nemesis to our heroic pair.

“If we made Link a female, we thought that would mess with the balance of the Triforce,” he said—never mind that the magical three-fold source capable of granting its wielder any wish they desired is already unbalanced, with men winning out two to one.

The outcry against Aonuma’s comments was far-reaching, inspiring essays, Twitter threads, and online analysis about all the reasons why the producer’s arguments weren’t stacking up. But all of that simmered down when Breath of the Wild finally released on the Nintendo Switch and Wii U in 2017. The game tapped into the series’ earliest conventions by providing an open world to the player outside of a linear storyline. You played as a version of Link who’d lost his memory and you could travel anywhere on the map in a number of ways—how you got there and how you adventured was entirely up to you.

For non-speedrunners and completionists, restoring Link’s memories after 100 years in isolation became much more than a simple gameplay mechanic. Each memory unlocks a cutscene that develops Zelda’s character in ways we’ve never seen before, allowing us to be privy to her doubts and dreams. There’s a clear tension between who she is as a royal heir, who she is as a scholar with an academic mind, and who she is as a divine being destined to defeat Ganon. It’s through these cutscenes we’re able to flesh out the disembodied voice calling to Link from Hyrule Castle, transforming her from a trope into a real, complex person.

At the end of the game, after taking down Ganon in a final fight, we’re made to believe Zelda’s powers have dwindled, and we’re left with a question of who she now is, at the end of the story. But before we dive into that and the promise of what a sequel might bring to the franchise, it’s important to take a look at how Zelda’s character has evolved up to this point and how all facets of her character—especially in Breath of the Wild—have evolved past the point of legend and into an era in which the active female character is just as fully fleshed out as the others who try to save her.

In the beginning, Shigeru Miyamoto made Zelda non-existent.

The Legend of Zelda was just that: a legend with minute detail. Skipping the instruction booklet and hitting start right way on the opening screen sets you off on an adventure as a young boy in a green tunic standing just south of a small cave in the middle of nowhere without any direction. But, if you linger at the opening screen, the reasons behind your adventure are made clear and kept simple:

“Long ago, Ganon, prince of darkness, stole the Triforce of Power. Princess Zelda of Hyrule broke the Triforce of Wisdom into eight pieces and hid them from Ganon before she was kidnapped by Ganon’s minions. Link, you must find the pieces and save Zelda.”

And so, in this first entry in the series you play as an everyman whose sole mission is to save a princess you know virtually nothing about. Throughout the game, as you crawl through a number of puzzling dungeons and scramble from one area to the next, your sole driving purpose is to save the girl. In essence, it’s the idea of Zelda that runs throughout the entirety of the game. She is the lore behind your adventure, an object of desire that gives you just enough reason to keep you going. It isn’t until the game’s final moments, after you land the final blow against pig-faced Ganon, that you find Zelda held prisoner behind a wall of flames. Before she even speaks, you know she’s the princess because, after all, she’s wearing a dress. She thanks you for saving her, calling you the hero of Hyrule, and then the credits roll. It’s an ending almost too abrupt for most games today—but according to Jennifer deWinter, director of Worcester Polytechnic Institute’s Interactive Media and Game Development program, it’s an ending that works.

“If you are Christian and you don’t meet God until the very end, does that make his presence less felt?” deWinter asks. “If the game is called Legend of Zelda, and all of your motivation is based on the existence of this thing, the experience and the process is going to be the most important because that’s where you’re spending all of your time and all of your growth, all of your exploration and all your discovery. It’s always defined by knowing what you’re moving toward.”

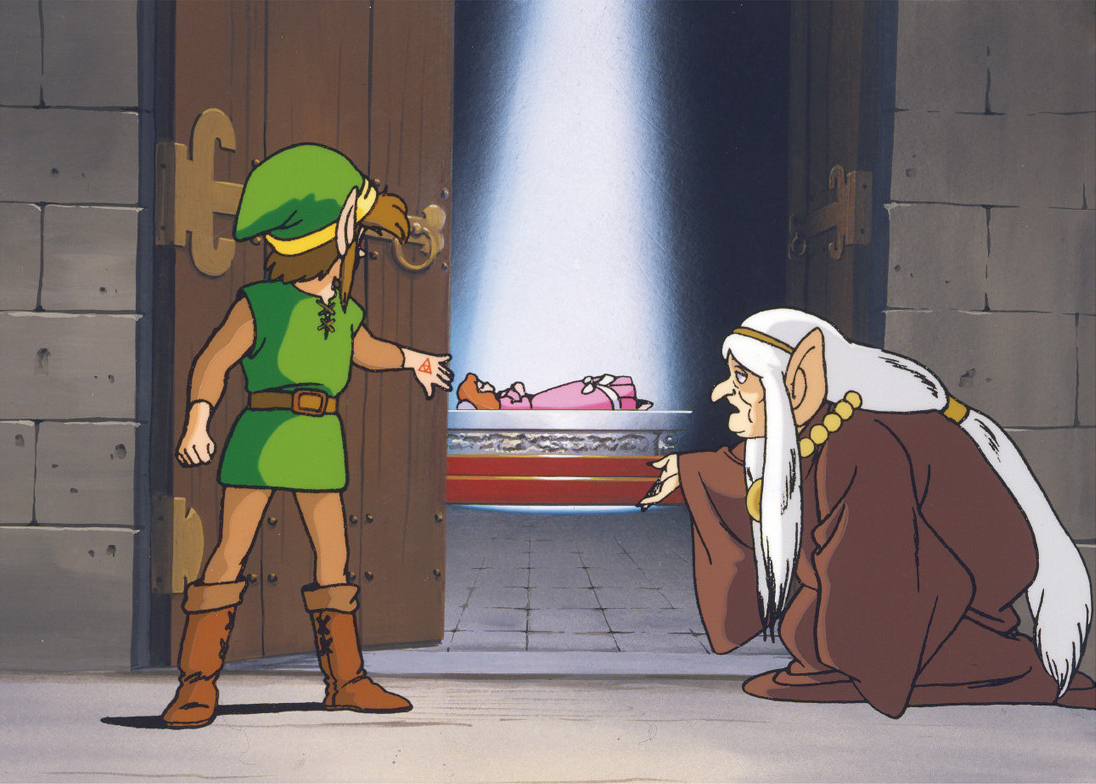

When we dive into The Legend of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, the rules of the first game no longer apply. Perhaps this is in part due to Miyamoto designing and directing less and stepping into the role of producer. Or perhaps they wrote themselves into a corner with the first game’s ending—we briefly met Zelda, so we can’t lose her now.

In this game, Zelda is placed in front of you from the very beginning. In fact, she’s the original Princess Zelda from which all other female descendants get their names (including the one you saved from the first game). She’s been hidden for years as a victim of a sleeping curse, preserved on a pedestal inside the temple where you begin your adventure. In a game that’s been critiqued heavily for its difficulty and departures from the original, it almost adds insult to injury that when you have a Game Over, you’re transported back here to this very temple and forced to be reminded of why you’re playing: You’re here to save the girl that’s just beyond your grasp.

“No one ever talks about Zelda II because it’s not as good,” says deWinter. “[Princess Zelda] becomes weaker. She becomes a sleeping beauty.”

In fact, it isn’t until The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time that the titular princess takes on a more active role.

Ocarina of Time was groundbreaking in that it further built off of Miyamoto and Aonuma’s history of incorporating nontraditional gameplay mechanics like music and song into a game without it feeling forced, and those gameplay mechanics drove a fresh new narrative. But, given all of its successes and its place in the series, it was still a game that relied heavily on traditional gender stereotypes, as pointed out by Emma Vossen, co-editor and co-author of the anthology Feminism in Play.

“The trailer for Ocarina of Time really sort of puts into place the idea of how Nintendo is imagining it and how they’re framing this game in games culture,” Vossen says.

The commercial Vossen is referring to alternates between gameplay, cutscenes, and old-timey narration that aggressively genders its audience by asking the question: “Willst thou get the girl? Or play like one?”

“It was this very stereotypical, ‘You’re a boy. Save the princess. She’s your love interest,’ whereas now, I’d like to think games culture is more complicated than that,” Vossen says. “We’re thinking about other things in a much more complicated way, so maybe people are ready for some more interesting ideas, more complicated ideas, about who’s playing these games and who can be played in the games.”

Even the land of Hyrule is aggressively gendered. You have an entire race of Gerudo who are Amazonian-like warriors so untrusting of men that you have to disguise yourself as a female to enter its desert city—and yet, when Ganondorf is born into their society, he is pushed up the hierarchy as their rightful ruler and completely subverts their own restrictions simply because he is a man.

And Ocarina’s Zelda is at the very center of this gendered Hyrule hierarchy. When we first find her in the court of Hyrule Castle, she’s a young girl peering through a window to spy on a secret meeting between her father and Ganondorf. Her father has ignored all of her warnings about Ganondorf’s plot to overthrow the royal family. Her intuition has been entirely overruled, and so she turns to young Link for help, gifting him with the ocarina, a royal family heirloom that boasts magical powers to unlock temples across the land and help Link time travel seven years into the future.

As an adult Link, you’re transported to a corrupt Hyrule in which Zelda has presumably gone missing. In an effort to seal Ganondorf away for good and return Hyrule to its former glory, a mysterious warrior named Sheik guides Link through a series of trials to reawaken sages powerful enough to get the job done. Before each temple, Sheik provides Link with the songs to access each dungeon and the wisdom to tackle each boss that awaits him. In every situation, it’s clear Sheik has been through these trials before—so it’s even more eye-opening and shocking when we learn late in the game that Sheik has actually been Zelda in disguise all along.

“There is this aspect that in the world of Zelda, there are still gendered expectations,” Vossen says. “It makes sense that to travel around the world like that, to do all those things, she has to disguise herself as a man because of these norms that have been established in that world.”

In some cases, the decision for Zelda to take on the identity of Sheik has sparked numerous online discussions about what exactly Zelda’s powers are—does she magically transform her feminine body into a masculine one in order to regain agency in this world? Or is she simply crossdressing?

“When she has this agency and ability to disguise herself, or has some alter ego, she’s actually super effective,” says Sarah Stang, essays editor at First Person Scholar and author of (Re-)Balancing the Triforce: Gender representation and androgynous masculinity in the Legend of Zelda series. “She’s this badass ninja warrior who enacts the role of hero by saving another princess.”

Indeed, when accessing the water temple for the first time as an adult, Link learns from Sheik that all of the Zora have been permanently frozen under ice and it was Sheik who saved its sole princess, Ruto, from suffering the same fate.

“Sheik also embodies that wise, guiding figure by teaching Link the songs he needs to succeed,” Stang says.

When Zelda reveals her true identity to Link in Ocarina of Time, she reverts back to her pink-laced gown and tiara, and within minutes of the reveal Ganondorf encapsulates her in a crystal and kidnaps her—forcing the player to yet again rescue her from the clutches of evil.

“When she is a pink dress-wearing, tiara-donning, long-blonde-haired beautiful princess, she is unable to enact the kind of agency she wants or agency she should be able to enact given how powerful she is,” says Stang, pointing to Joan of Arc and Mulan as historical examples of this tired trope. “When she becomes the princess again and becomes normatively female, she loses her agency almost instantly.”

The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker follows suit, although it begins with a markedly more progressive approach. In this game, Tetra is the freest female character in the entirety of the series, a bold captain leading a band of pirates on adventures across the high seas. Throughout the game, she’s brash and brazen, challenging Link whenever they cross paths in a rambunctious and playful way that establishes their relationship as more equal than previous games. Tetra is loud and aggressive, taking actions long before Link is able to make decisions on his own. But in the endgame, it’s revealed that her memories had been wiped to keep her safe and that she is in fact Zelda, the daughter of Hyrule.

“In Wind Waker, when she is revealed to be Princess Zelda, she doesn’t choose to reveal herself, she’s forcefully transformed into Princess Zelda,” Stang says.

It’s a moment that’s jarring, terrifying and quite physical: Her skin gets lighter, her hair turns a brighter shade of blonde and untangles to reveal longer curls, and she’s suddenly wearing makeup and jewelry, once again forced back into a pink dress.

“She’s physically transformed into something that embodies, not only normative femininity, but stereotypical princesses, and she’s forced to stay behind,” Stang says. “The king, this man she barely knows, tells her, ‘No, it’s not safe for you anymore. You have to stay behind.’ So she can no longer adventure with Link and help him. She no longer has her pirate band. She no longer has anything—she’s completely disempowered.”

It’s ironic then that when you return to her later in the game, Ganondorf has found her anyway, despite the attempts to keep her hidden and off the grid. He’s put her to sleep, and she even apologizes to Link for her own victimization.

“She becomes this milquetoast,” Stang says.

In the direct sequel Phantom Hourglass, Zelda regains her identity as Tetra, refuting the title of Princess when her crew calls upon her at the beginning of the game. She screams at them to never call her that again because it represents everything that marks her incapable of achieving true freedom. And when she spends the rest of the game turned to stone, it’s yet another example that Zelda’s body is not ever her own throughout the entirety of the series.

In Spirit Tracks, we revisit the world of Wind Waker and Phantom Hourglass generations later, with a Princess Zelda who embodies all of the familiar feminine traits. In this game, Zelda accompanies you throughout the entire adventure as your sidekick, albeit as a spirit who’s desperate to get her body back after it was stolen and possessed by the Demon King.

After discovering she might lose her body permanently, she flies around the room in an overly dramatic panic, shrieking that it’s up to Link to save her body and bring it back for her. “I will wait for you here,” she says, eyes wide in fright. “That’s what princesses have always done. From what I understand, it’s kind of a family tradition.”

Thankfully, she’s coaxed to join Link and discovers she can fight alongside him by possessing hyper-masculine statues with enormous swords—a seeming overcompensation for having lost her own body and subsequently her strength.

In an interview with The Telegraph, Aonuma acknowledged that Zelda’s role in Spirit Tracks is probably the most pronounced she’s had in the series up to that point.

“So far, she’s been invisible to players during the game, making it impossible for them to find out what kind of character Zelda is,” Aonuma said. “This time around, because you are traveling with her all the time, she’s going to be vividly identified. You might even begin to wonder if Zelda is the biggest hero of the game, rather than Link.”

But in the end, she’s incapable of taking back her own body without praying to her grandmother Tetra and asking her to bestow her with strength—a move, it seems, that’s more metacommentary on the fact that she’s strongest when she takes control of her own destiny in spite of the universe threatening to control her.

“She’s been put to sleep, imprisoned in a crystal, turned to stone, turned into a painting, she’s lost her body and on and on,” Stang says. “It’s like she’s being taught a lesson for trying to be too independent.”

It’s this lesson that’s made most prevalent in Breath of the Wild, in which we’re given a version of Zelda who struggles to discover who she is on three very distinct levels: that of an intelligent academically-minded woman; that of a princess and figurehead of the royal family; and that of a divine, spiritual being bestowed with unimaginable power.

Throughout each of the game’s acquired cutscenes, we see Zelda struggle with embodying each of these various facets of her identity. She sets out to research ancient robotic Guardians and find a way to use their long lost technology to her advantage against the rising threat of Calamity Ganon—but she’s barred from doing so by her own father, who wishes for her to rely on age-old traditions passed down by their family instead. These traditions require Zelda to travel across the land and pray to the goddess Hylia for strength in order to access her slumbering power, a requirement that has no need for her brain but for her unending devotion. But even her prayers fail her.

In one cutscene, she reminisces about how she’s been told her whole life that she would carry the same power of her grandmother and mother, and how her father told her to “quit wasting your time playing at being a scholar.”

“I’ve spent every day of my life dedicated to praying,” she says. “I’ve pleaded to the spirits tied to the ancient gods and still the holy powers have proven deaf to my devotion. Please just tell me, what is it? What’s wrong with me?!”

It’s a heartfelt moment that centers Zelda’s own internal struggle with her identity—and it’s a struggle accessed only through optional cutscenes meant for the player’s consumption. Viewed one way, these cutscenes are an invasive, easily overlooked part of the story, but they feel as if they’re meant to be so much more than that.

“She’s interesting in that she’s trying to challenge things,” Stang says. “She’s almost challenging the lore of her own universe and of her own story.”

In another cutscene, we learn that it’s only when Link’s own life is at risk that Zelda’s powers awaken. Just before an enormous Guardian sets its sights on a battle-worn Link, she shouts with her hand raised to the sky, sending her power out across Hyrule and shutting down all guardians within reach. It’s a moment that begs for analysis: What caused her to awaken her power in that moment?

“My positive theory is that when she actually has to act instead of sitting there praying and thinking, it just works: she’s accessing her instincts, so she’s figuring out how to get past that sort of self-doubt and self-loathing that’s followed her through her life,” Vossen says. “My negative theory is more likely considering how Nintendo has framed Zelda in the past: She loves Link and in this moment, it was the power of love that allowed her to access her powers.”

Despite the reasons behind the resurgence of her powers, by the end of the game, Zelda herself is left powerless.

After sealing Ganon away, Zelda turns to Link and calls him the hero of Hyrule, asking if he really remembers her. Depending on how you’ve played, it might feel like a throwaway line. But those of us who’ve unlocked all Link’s memories and completed all story missions are then given access to the true ending.

While standing on a cliff overlooking the kingdom of Hyrule, Zelda talks about how there’s still so much more to do.

“I believe in my heart that if all of us work together, we can restore Hyrule to its former glory,” she says.

As they begin to walk back to their horses, Zelda pauses for a moment.

“I can no longer hear the voice inside the sword,” she says, referring to Link’s Master Sword, often the key to his power. “I suppose it would make sense if my power had dwindled over the past 100 years.”

She turns to Link once more with a saddened look as if she’s pondering what that means, but then she smiles as if she’s let go of her doubts.

“I’m surprised to admit it but I can accept that,” she says with a nod. She laughs and the camera pans out as they walk toward the horizon and whatever new adventure awaits them.

It’s a moment, deWinter says, that’s both empowering and disempowering. Zelda is finally free, but she’s lost the very gift that makes her who she is.

“You can never celebrate something without seeing a stern underbelly,” deWinter says. “It’s always ambivalent. It’s both the good thing you can see and the terrible thing you can see because this is how ideology and sexism work. We both get the angel in the tower and the isolated hyper-controlled female.”

But is it even possible to suggest that, coming out of this ending, we might be given the chance to play as Zelda in the sequel? DeWinter suggests it’s no small task if Zelda retains her powers. If the win-state of any of the traditional Zelda games is Zelda, she says, deciding the win-state for a playable Zelda character seems insurmountable.

“If Zelda is playable, she’s all powerful,” says deWinter. “If she’s all powerful, what’s the game? You either have no game or you have the amplification of the game into ludicrousness. You have a game that destroys the world so much, that every game after that has to reset and create a new origin story.”

Perhaps there is hope then, in that Breath of the Wild seems to follow the miko narrative seen throughout Japanese popular culture. We see it in Kagome and Kikyo in Inuyasha and even in Colette Brunel from Tales of Symphonia, who’s raised with the knowledge that she is the Chosen one destined to die in order to save the world.

Derived from Shintoism, the miko is a spiritual maiden born with a connection to animistic forces beyond her control. “You’ll get a lot of narratives about this tension between being a spiritual maiden and being a whole human who wants to be able to do other things and these are often in tension with each other,” deWinter says. “These will often fracture the identity and it is only through bringing the identity together that you can save that character.”

In most cases, that power is expelled by the end of the narrative, returning the maiden to a normal life. In some cases, the maiden must die along with her power. But, it’s not often we continue the miko narrative after the power is lost—and the sequel to the Breath of the Wild seems to do just that by asking who Zelda is now that she’s powerless. If this were any traditional miko narrative, deWinter suggests Zelda would revert back to being the simple royal daughter of Hyrule, maybe even a scholar.

“She gets to live a normal human life,” deWinter says. “She doesn’t have to save the world anymore.”

However it pans out, for the first time in the entirety of the series, Zelda is a complete clean slate. Her character has achieved that which Link has had from the very beginning—a sense of normalcy, of wonder, a sense of relatability.

“The ending [of Breath of the Wild] could set up something really interesting where she thinks the power is gone and she’s okay with it because it represents something negative,” Vossen says. “But maybe she comes back around to that power in her own terms, in her own time, in her own way.”

In essence, a Zelda that sets off to define her own identity is a character we’ve been grasping for since the very beginning. Now, more than ever, we’re armed and ready for it.

“There’s something so feminist about that idea that I kind of cannot believe it’s even possible that Nintendo would do it,” says Vossen, laughing. “People have been ready to play as Zelda for a really long time. Now, maybe Nintendo will catch up with us.”

All images: Nintendo

An earlier version of this story mistakenly referred to Sarah Stang as the founder of First Person Scholar. She is the publication’s essays editor.

James Bigley II won the City and Regional Magazine National Writer of the Year Award in 2018 and his work, largely focused on human interest stories, has been published in Cleveland Magazine. He’s been in pursuit of the Triforce of Courage for more than 20 years. You can find him on Twitter @Jc_bigz.