This article contains spoilers for What Remains of Edith Finch, Rime, and Arise: A Simple Story.

As sure as you are reading these words on this page right now, as seamlessly as each letter collaborates with those before and after it to form words, sentences, ideas in your mind, you will one day in the future lose all ability to do so. It’s likely you won’t know when it will happen or who will witness it or perhaps even why it happened at all. Like a computer unplugged by an errant leg, the lights will go out, the display will flicker out, and the power button won’t fix any of it. In one very specific moment in the future, you will die. After, you’ll spend a lot more time dead than you ever spent alive. So will I. So will everyone you’ve ever met, ever loved, ever missed. Viewed in morbid terms, life is a series of introductions to future dead people.

We all basically understand this, so why does death still bear so much weight on our collective shoulders? We flee from addressing its inevitability, awkwardly whistle past the graveyard, and despair whenever we’re painfully reminded of the inescapable conclusion to each of our stories. After hundreds of thousands of years of grappling with the subject, the human race is still afflicted with the curse of understanding its own promised demise. It’s the burden of high-functioning sentience in a world comprised mostly of animals that know only to survive the moment. We can’t see the whole road ahead, but we uniquely understand where it ends.

In order to try and find solace in that final, fatal bus stop, humans have turned to art for as long as we’ve recorded our history. Far from its early days of almost exclusively cartoonish heroes squashing nameless baddies, video games have grown—and grown up—a lot over their young but meteoric rise as an art form. Today’s games are often at their most thoughtful in the indie space, where smaller teams can find refuge from publishers that demand catch-all power fantasies. It’s in indie games where I’ve found some of the most thoughtful meditations on the few universalities of life: love, loss, and grief.

According to Ian Dallas, director of What Remains of Edith Finch, Giant Sparrow’s adventure game about a family that can’t help but die in uncommon tragedies, was born from an unlikely spark after he went diving in Puget Sound. “Seeing the bottom slope away into an infinite darkness,” he told me, was “simultaneously beautiful but also overwhelming.” He knew then that this would become the spark for the studio’s next game. “We started by making a scuba diving simulator and then kept making different prototypes that evoked that feeling.”

You needn’t take diving lessons to know the feeling. It’s the sort of existential dread one can find in many moments in life: getting lost in a crowd as a child, the split-second just before a car crash, receiving news of a loved one’s terminal illness. It’s the feeling that everything you know could go away in a hurry. In Edith Finch, players re-experience this feeling roughly every 10 minutes throughout its two-hour runtime, even as its characters never seem to see the cruel punchline coming.

Credit: Giant Sparrow, Annapurna Interactive

Sometimes you’re a little girl who has, in her unjust famine, taken to eating toxic foods. Other times, you’re a boy who dares to fly, and promptly does so when he is flung off his swing, absurdly built on a cliffside. In one of the most memorable scenes in Edith Finch, you’re a young man, working at a fish market, systematically chopping off their heads on an assembly line while your mind races with drug-addled dreams of gilded fanfare in your honor. When these hallucinations, joyous as they seem, overtake the real world entirely, the young man slips up and delivers himself to the same fate he handed so many fish.

The Finch family responds to these deaths and others by labeling themselves cursed and locking the doors leading to the rooms of any and all deceased for years and years. It’s an unhealthy coping mechanic, to lock away the sight of things and blame cosmic bad luck, and Dallas made it clear Edith Finch props up the allegedly hexed family as a cautionary tale. “I’d hope that we confront grief by being honest with ourselves about it,” he said. “As humans, we want simple, causal explanations for everything but unfortunately reality is much stranger and more complicated than we can understand.”

Credit: Giant Sparrow, Annapurna Interactive

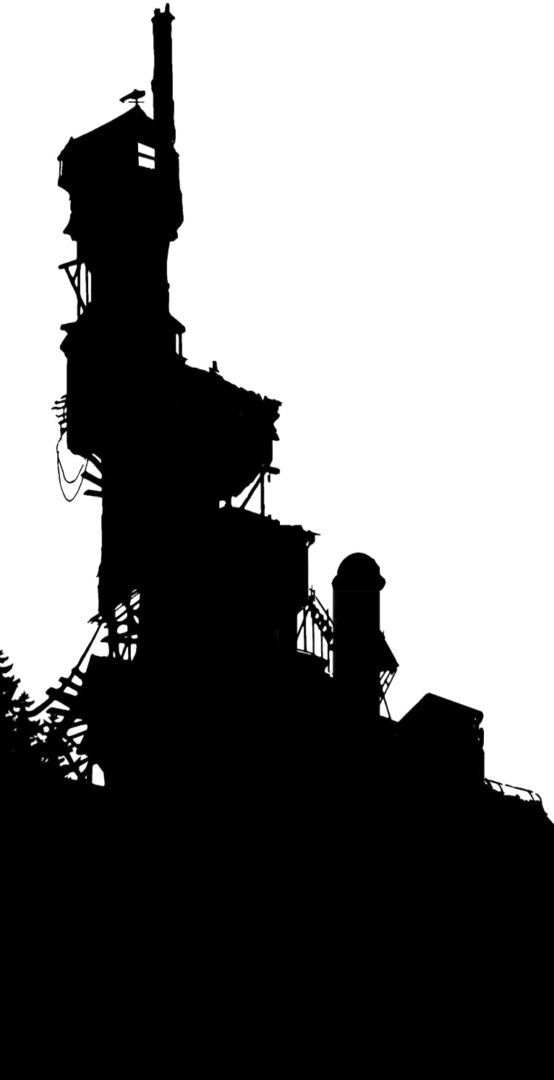

A curse would be so easy, but a curse doesn’t allow for the grieving process to advance through its necessary stages. The Finches exist as a monument to the first stage of grief in the model popularized be psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross: denial. The Pacific Northwestern family couldn’t even move onto anger, because the first stage was prolonged for literally years and years. The Finches didn’t really grieve at all. Rather, they created a fantasy world to escape to, where the lies they told themselves grew as tall as their architecturally impossible home.

When I asked Dallas if he took inspiration from grief he experienced in his own life, he spoke of the death of his mother, to whom the game is dedicated in the credits. “My mother died of ovarian cancer a year into development on Edith Finch though I’m not sure how much of a direct inspiration that was [since the game was] pretty far along by then,” he told me. “It made it easier to write about reactions to grief having recently experienced it myself.” He also said he hopes his process was healthier and less dramatic than the subjects of his adventure game.

Dallas’ words on the subject are well reflected in Edith Finch. Several times, he referred to the ambiguity of death and the imprecision of grief, even with the guide arrow of the Kübler-Ross model. He said the Finches’ world of magical realism was a fitting analogue for death as an otherworldly, supernatural force and admitted he doesn’t believe there is a best way to deal with grief, though he added there seem to be some ways that are worse than others. “The extreme responses of trying to ignore it or of thinking endlessly about your grief seem like they’re unlikely to be helpful. Hopefully our game gives players a range of responses to think about, as a way of understanding what feels best to them.”

In all of video games, there’s no more obsessive meditation on grief than Tequila Works’ gorgeous 2017 puzzle-platformer, Rime. As the stories in Edith Finch and Rime grapple with similar themes but in very different ways, I reached out to one of the game’s writers, Rob Yescombe, to try and understand how he came to different conclusions regarding the grieving process. Unlike Dallas’ more laissez-faire approach, Yescombe’s Rime script carries players through the five stages of grief, ending with one hell of a final scene.

“The job of a writer is, in part, therapist,” Yescombe told me. “Initially, [Tequila Works] intended to make something purely gentle and bright, and that certainly attracted me, but I wanted to find out why we wanted to make something like that.”

As Yescombe and the studio’s creative director Raul Rubio inspected their motivations, they realized they were using the more soothing original pitch as a shield, protecting them from their own aging and all that comes with it. “Once we accepted that, we knew we had a responsibility to leave that state of denial—and that would be the purpose of the game.”

Credit: Tequila Works, Grey Box, Six Foot

Rime uses the five stages model as foundation for level design, with each of the game’s five chapters wordlessly carrying players through the stages. Yescombe told me Rubio gave the team free rein to express the stages how they see fit, so the end result became a “mosaic of grief that was both ambiguous and specific.”

Like Dallas, Yescombe’s contribution to his team’s morose mosaic was the death of his mother, as well as the death of his “inner child” during that grieving process. But it wasn’t only this corporeal loss he suffered that inspired Yescombe, he told me. “It was also about my fear of creative death—that getting older and taking on new responsibilities might somehow render me unable to make art.”

The theme of responsibility is as important as grief by the end of Rime, as it’s the father in the story who is grieving a tremendous loss, not—as we’re led to believe for four hours and 55 minutes of the five-hour game—the child. The narrative twist is a stunner to all who play Rime, but because it grapples with its subject matter so well, it’s not a game that relies on that twist. As it’s revealed that the father lost his son when their sailboat got caught in a violent storm, players revisit the fateful scene already shown earlier. In this final iteration, the truth is revealed. The father desperately clings to his son as he falls overboard, helpless to watch as the boy plunges into a salty, horrific void, lost forever at sea. It’s a father’s responsibility to take care of his child, and as a dad myself, no scene in video games has ever stayed with me longer than these painful moments.

But there is a cathartic light at the end of Rime’s tunnel. Following the flashback, the game’s final scene keeps us out of the fantasy world depicted for most of the game and puts us into the real world as the father moves into the acceptance stage. “We wanted to show the ‘real’ world, because we wanted to gently encourage players to consider the impact of grief on their own real world,” said Yescombe. “I think, deep down, players always know where the game is going—even if the truth is only revealed at the end. We know where life goes: death. But it still feels like a twist when we get there.”

Credit: Tequila Works, Grey Box, Six Foot

Rime’s story is harrowing and hopeful in equal measure, which is a difficult needle to thread. Yescombe spoke a lot about grief as healing, and that duality is the central pillar to Rime. The father’s anguish has visibly exhausted him by the end of the game, and yet, as he lets the torn cloth from his son’s coat get carried out to sea, this time as an act not of impotence, but acceptance, the game asks us to find a way to go on should we ever find ourselves in a similar hole. “For me, the wonderful thing about grief is that I emerged from the worst of it. That gives a new perspective on future suffering—and the ways one might help others through it.” Does time heal all wounds? I asked Yescombe. “They stop bleeding. I’m not sure that’s the same as being healed. But that experience helps us tend the wounds of other people.”

Like Rime and Edith Finch, a most recent example of a game swimming in the deep waters of grief is Piccolo Studio’s Arise: A Simple Story. Like those other games, Arise offers its own interpretation of love, loss, and moving on. The story of Arise plays out similarly to that of Rime, only instead of moving through the five stages of grief, players relive the most important moments of a dying man’s life. Along the way, the singular constant is his true love. From the earliest days of the characters growing infatuated with each other as children, players pass through the old man’s most crucial memories through the decades they spent in love.

Naturally, we don’t forget the bad parts when we grow up, and Arise reflects that. “We wanted to create a universal story that talked about the ups and downs of life, to be an emotional rollercoaster,” said Alexis Corominas, who co-directed Arise with Jordi Ministral. “Most games star a young hero with the promise of adventure ahead. An old man was a lot more interesting, though: He has a lot of time and memories behind him and less future ahead, so he’s forced to look back.”

When I suggested Arise is actually more about love than about grief, the directors agreed, but offered a caveat. “And what’s more universal than love?” asked Corominas rhetorically. “You don’t learn to love, you can’t forget it, you can’t measure it, it’s not a rational thing, it’s not something you choose to do.” But love, he added, is “one side of the coin.” The other is grief. “Where there is love, there’s heartbreak and loss.”

Credit: Piccolo, Techland

This outlook is displayed in Arise most notably when the loving couple’s baby dies. Revisiting the man’s memories, the details are left vague, but the metaphorical platforming levels, which had just before danced with players through lovestruck, moonlit lakes and hopped along the symbolic heartbeats of the incoming newborn, suddenly grow cold, dark, distant. Land masses break apart like continental drift, signifying the couple’s struggle to remain together following such a tragedy. It’s in these memories where the old man struggles with grief, but the tragedy hits his partner even harder, and it becomes his job to pull her out of that dark place.

“In the first six chapters of Arise, in all statues and memories, it’s she who has the active role. It’s she who first talks to him, who guides him, who leads the way,” Corominas said. “When tragedy strikes, she’s devastated and gives up. It’s he who stands up and carries her on… When one weakens, the other one has to step up.”

I asked them the same question I posed to Dallas and Yescombe about their real-life grief, and they too alluded to the inevitability of loss. “We all have lost people we loved. We all love people. We all will depart. That happens to every human being, but everyone has its own grieving process. While we were making the game at Piccolo, we tried to find what was common to all of us, how we faced adversity: by loving someone.” Are we right to fear the grief process, to run from loss? I asked the pair. Ministral didn’t think so. “There are many cultures that celebrate death… We should learn to celebrate more and fear less.”

Credit: Piccolo, Techland

If Arise seems like the most hopeful of the three grief stories, that’s because it certainly is. The game’s closing optimism—the final scene depicts the family of three reunited in some way —was so obviously different than other games’ treatment of the same themes that it became the catalyst for me to seek out this story. That optimism, so above and beyond even the other healthy perspectives I received, was a recurring theme when I spoke to the co-directors. “Even though it seems a cruel universe to live in, actually we see it the other way around: It’s a good universe to live in, because where there is grief, there’s love!” Corominas excitedly told me. “It should be uplifting to think that the saddest moments in life happen because of the best ones. In a merciless and ruthless universe, we have found love, and we should celebrate it!”

The happily-ever-after ending is open to player interpretation, even as the directors agree when we see the trio reunited in the final scene, we’re merely seeing the grown man’s last, most beloved image of his life, his “final stone” they say. Religious and laic interpretations are equally valid to them, even as they write from a secular point of view. “It’s this togetherness that matters the most in the end, regardless of your own interpretation of the images presented,” Ministral told me. “In the final scene, the old man simply finds a final image, the one that best represents his life, the one he likes the most as the end of the road: the old woman and the baby.”

So does that make Arise a sad story or a happy one? “It’s both,” Corominas said, “because it’s a depiction of life and life is a bittersweet thing.”

The reflection of each creator’s perspective in their work proves one really does write what they know. Edith Finch’s messy, supernatural peer into the void is much like Ian Dallas’ own existential dive in Puget Sound. The game deliberately shys from providing answers because Dallas believes there’s no textbook on how to overcome tremendous loss. Rime plays out Yescombe’s perseverance through losses both tangible and spiritual and helps players and protagonists alike learn how to let go. Arise reminds us that there is no light without darkness, and Corominas and Ministral’s shared optimism gives us a grief story with the brightest light at the end of the tunnel.

Of course, these aren’t the only games to grapple with grief. Recent indie hit Gris tells a story somewhat like Rime’s, with levels that represent each of the five stages as a young woman mourns an ambiguous death in her own life. And some big-budget games have managed to contextualize personal tragedies as well. In The Last of Us, for instance, we see Joel begin to move on from his daughter’s death 20 years prior once he meets Ellie. In Mass Effect 3, it’s your former crewmate Thane who must grapple with his own impending death. In one respect, Thane is the closest embodiment of the five stages: Kübler-Ross’s original model was designed not for the grieving survivors, but for those dying themselves. Games have long treated death as an objective, something players deal out as a means to victory. Increasingly, designers are also confronting its emotional aftermath.

What Remains of Edith Finch, Rime, and Arise: A Simple Story all depict grief in drastically different ways, and yet they all end on a similar note: acceptance. Kübler-Ross identified acceptance as the final stage of the grieving process, but we see in these games that it takes many forms—none of which need to be mutually exclusive. From Edith Finch we can accept that no one really knows anything, and we can’t claim to know what stares back at us from the infinite darkness. From Rime, we can accept that what’s done is done, and though we will never live without it, we must learn to live with it. From Arise, we can accept that how we spend our time is more important than how our time ends.

Cosmic deference, cathartic self-inspection, and unflinching optimism—three coexisting paths to moving on.

Header image credit: What Remains of Edith Finch; Giant Sparrow, Annapurna Interactive

Mark is a Boston native now living in Portland, Oregon. Formerly the features and reviews editor of TrueAchievements, he’s been writing online since 2011 and continues to do so as a freelancer today for outlets like EGM, GamesRadar, and OpenCritic. Outside of games, he is an avid biker, a loud animal advocate, an HBO binge-watcher, and a lucky family man.