When we think of animals in games, we usually think of anthropomorphized cartoon beasts like Sonic or Donkey Kong. While these characters may outwardly resemble animals, they have little in common with actual wildlife. Look past the fur, and you’ll see that their behaviors, their expressions, and the goals they aim to achieve are all relatably human.

Animals, real animals, rarely take center stage. When they’re friendly, games mostly employ them as background details—if we’re lucky we can pet the dog—or reduce them to buddies or modes of transport for humans. Iconic series such as The Legend of Zelda, Fallout, The Witcher, and Metal Gear Solid all know the value of a trusty steed or a faithful canine companion. Even more commonly, animals appear as enemies to kill or resources to gather. In countless action games or open-world RPGs, including some of those just mentioned, we do battle against instantly hostile creatures like bats and bears, or our need for armor upgrades takes priority over the lives of the deer and bunnies populating the countryside.

Opportunities to play as a more grounded animal lead do exist, but they’re scattered lightly throughout gaming history. It’s a short enough list that a developer looking to design an animal character today might not find many past examples to draw on.

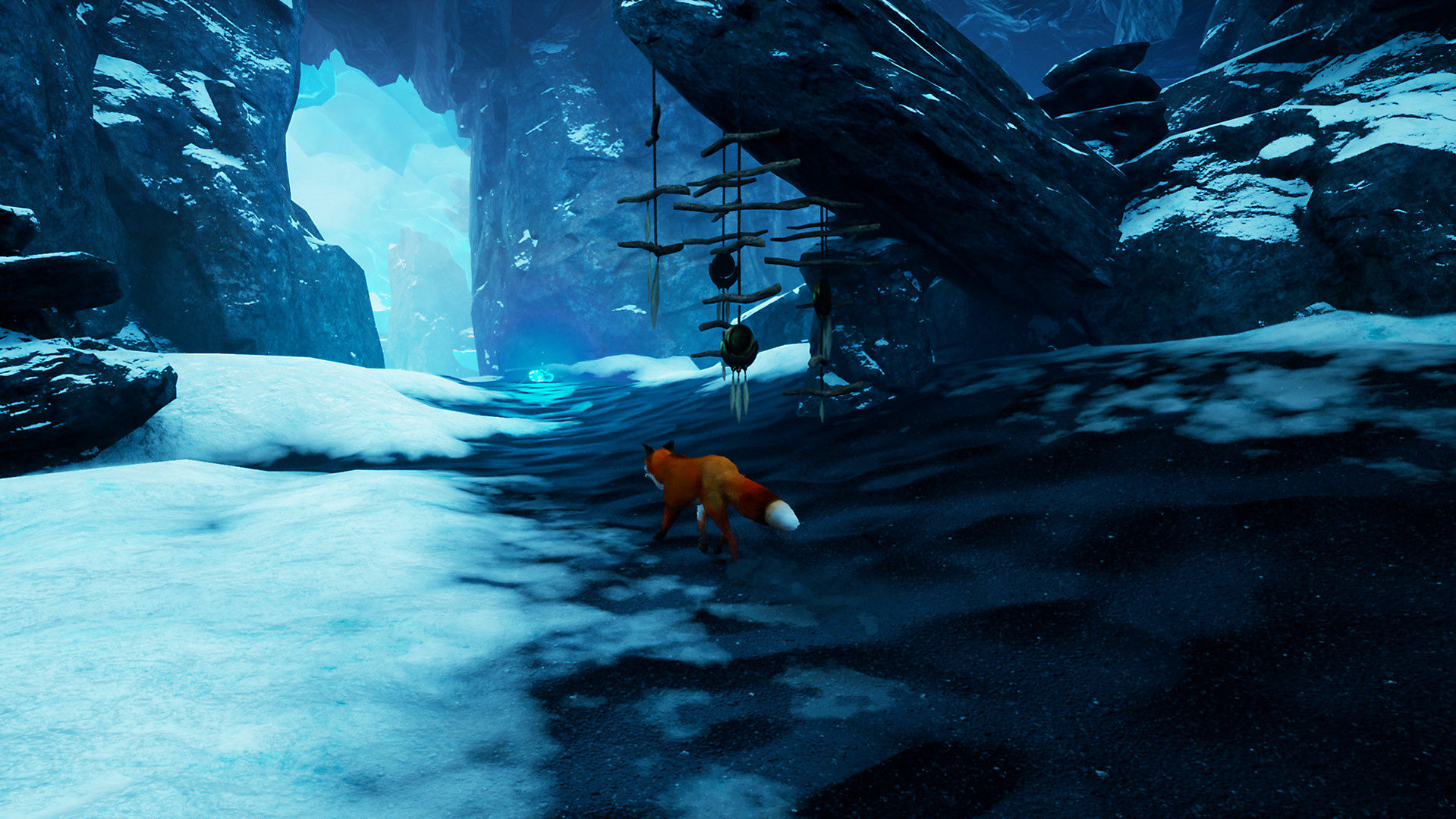

Such was the case for Infuse Studios when it built the 2019 fox-based adventure Spirit of the North. “We actually haven’t played very many games with animal protagonists that ran on all fours,” said Infuse co-founder Jacob Sutton. Clover Studio’s Ōkami, as Sutton noted, is one example, but there really aren’t many games which focus on a quadrupedal mammal.

Credit: Infuse Studio

It’s perhaps surprising that animal-led games aren’t more common, especially since they’re so well suited to creating novel experiences and offering different, interesting perspectives on the world. Even the earliest and most basic examples hint at the potential of such an approach. Take 1981’s Frogger, in which players must guide a series of frogs across a busy freeway and back to the safety of their lily pads. Though simple, the objectives and mechanics established a precedent of forcing us to see and relate to the world differently. In some small way, we adopt the animal’s perspective, which then reflects back on our own human viewpoint.

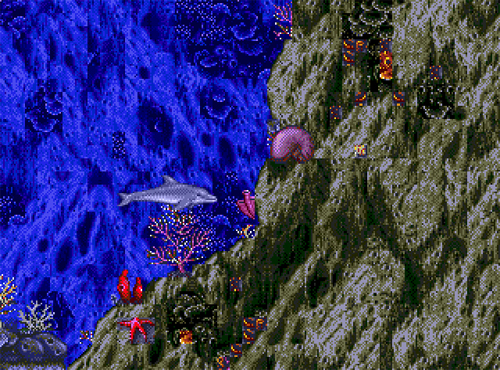

Credit: Sega

We can see how these concepts evolve in 1992’s Ecco the Dolphin. There’s nothing much realistic about Ecco’s plot, which revolves around time machines, ancient beings, and aliens. But from the name of the title character to the storyline about the oceans being drained of life, it’s not hard to spot underlying links to environmentalism. Beyond that, this is a game that accentuates a sense of embodying a non-human through its controls. The way Ecco cuts through the water, leaping and diving in smooth arcs, is tricky to master but creates a unique and liberating feel.

Alternatively, when games put animal characters in direct contact with humans, they can use the unusual perspective and attributes of their characters to highlight how the needs or desires of different species can clash. This is true even when the portrayals of animals are less realistic, such as in the PS2 titles Dog’s Life and Mister Mosquito. Or in Ōkami, where we actually play as a God in wolf form and have mystical powers. Here, the character works as a symbol of nature and its relationship to people, as we strive to paint the world back to a state of flourishing beauty.

Credit: Capcom

There have also been games that dip into the more brutal reality of nature. The Shelter series and Tokyo Jungle are two examples in which animals hunt and kill each other to survive. But even these premises provide elements of humanity to reflect on. Tokyo Jungle, for instance, becomes a metaphor about civilization thanks to its post-apocalyptic city setting, which represents the alternately individualistic and group mentalities that govern modern urban life. Its ending, which casts you in the role of a robotic guard dog, has something to say about the incompatibility between animals and human technology.

One contemporary animal game, the forthcoming Away: The Survival Series, takes some cues from these latter games in particular. André-Paul Johnson, head of growth at Canadian developer Breaking Walls, told me that Away “drew some inspiration from a few classic animal-based games, such as Deadly Creatures’ combat systems, Tokyo Jungle’s survival mechanics, and Shelter 2’s family dynamics. These games all have vastly different gameplay and mechanics, but they each bring an interesting perspective on what it’s like to play as animals.”

But Away is not merely a survival sim. As with many previous animal games, it uses its setting to say something about humanity and the realities of environmental crisis. Along with Spirit of the North, it’s part of a recent spate of animal games that continue and develop the thematic strands running through those earlier titles. They bring to light different modes of self-expression that force us to think differently about what we’re trying to accomplish. Not only is the experience refreshing, but it’s also a means to evaluate humanity from the outside.

Credit: Breaking Walls

In some recent examples, such as Ape Out, Untitled Goose Game, and the impending shark RPG Maneater, animals confront people directly. These games highlight an uneasiness or outright hostility between man and beast, whether that means disturbing people’s self-important routines or embarking on a bloody killing spree. In simple terms, they work as power fantasies, in some way fulfilling repressed desires to strike back and disrupt the status quo that we can’t realize in reality.

Conversely, games such as Spirit of the North and Away, as well as another recent release, Lost Ember, take a more abstract and contemplative approach to humanity’s relationship with nature, using animal characters to place people at a distance, so that we can better examine ourselves through their eyes. This latter group of titles, in particular, share a perspective that explores civilization from the vantage of nature to better survey the contradictions of human behavior and our impact on the world.

Here, even the choice of the central animal implies certain ideas and feelings. In deciding to make Lost Ember’s main character a wolf, for example, Mooneye Studios CEO and founder Tobias Graff cited two motivations. “The first reason is pretty simple and I think we can all agree: Wolves are awesome!” he said. But the selection is also intended to link the animal and human worlds, he told me, in a story about reincarnation. “Wolves or wolf-like animals like jackals are common figures in a lot of religions and myths and as such have naturally mystical features. We figured that would be a perfect fit for a story in which you have to figure out who you were and if the choices you made were the right ones,” Graff said.

Credit: Mooneye Studios

For Spirit of the North, Sutton said, “We knew we wanted to make a game with very little to no dialogue and have a unique character.” Again, the choice of a fox helped connect the natural world to civilization via the animal’s symbolic meaning. “The mythology that Spirit of the North is based on is the Finnish legend of ‘Tulikettu.’ According to the legend when the ‘Fire Fox’ runs in the snowy hills its fur and tail brushes up against things would create sparks that fly into the skies and turn into the Northern Lights.” Using animals with a significant cultural presence helps bring in wider themes.

Away’s sugar glider—a small marsupial resembling a flying squirrel—may seem like a less obvious choice for a leading character, but it was a pick well suited to the sensations the game’s developer wants to convey. Johnson said the team “wanted to craft an immersive experience where you truly feel like you’re part of nature.” In this sense, “as an animal that can walk on land, climb trees, and even glide through the air, the sugar glider lets you explore your environments in any way you choose.” As with something like Ecco, there’s a promise here of fluidity and agility that should create a sense of natural freedom in contrast with human behavioral norms.

The animals in all three of these games thus establish the base from which their perspectives on humanity can develop. For Lost Ember and Spirit of the North, concepts of mysticism and spirit worlds frame the reciprocal bond between people and animals. Both games use this spiritual side similarly, showing us fragments of a past civilization that now lies in ruins. With a kind of “future perfect” tense to their narratives, they project into an imagined world to come where only nature survives, and then have us look back to decipher what happened. It’s a method that points to the fragility and temporality of our position in the world—and offers a warning to be heeded.

For Sutton, the perspective in Spirit of the North, “helps tell the story of mankind’s dependence on things that they take for granted, things that could easily disappear or be unsustainable. It also helps sell the point of there really not being anyone left of the civilization as well.” Plus it’s a useful way of creating ambiguity, or an invitation to consider what can go wrong without being fed conclusive information. “Due to the way the story is presented to the player and not exactly told outright they get to come up with their own ideas of what happened in the past that made things how they are,” Sutton said.

Credit: Mooneye Studios

With Lost Ember, the key theme is transformation, as the wolf shape-shifts into various animal bodies to navigate different scenery and conditions. On this journey you uncover memories of the human soul trapped within the wolf, learning about how she lived and her role in the now-ruined civilization. It’s a story told from outside the events themselves, which shows us varied interpretations of the same actions so that we continually reevaluate what we’ve seen.

The transformation mechanic is key to that idea. “To question your own actions or even your view of the world and try and see it from a different angle was an important message for us to get across,” Graff said. “The gameplay supports this message by allowing you to see the world around you from high above as a parrot or from the ground level as a wombat and in between as lots of other animals. In that way the soul wandering ability—as we call it—is less of a gameplay or puzzle mechanic and more a way to underline what the game is really about.”

Away seems to offer a similar approach to its subject matter, despite adopting a more scientifically grounded scenario, especially in its representation of climate change. “Whether it’s through ancient relics and artefacts scattered around the world or through the game’s environments and climate itself, Away brings players to reflect on the consequences of global warming on nature, humans, and the animal kingdom,” Johnson said. Again, animal perspectives are used to judge humanity through its effects on the planet in a way that creates space for reflection.

What comes across in these responses is how well-suited animals are to representing themes of uncertainty, change, and potential disaster that mirror our view of civilization’s future. For Graff, “having a story that’s not clearly communicated by a human protagonist that just tells you what’s going on made it possible for players to create their own interpretations of different story elements and connect even deeper with its world.” Animals are naturally silent protagonists that experience human culture as alien, making them ideal for a story that asks as many questions as it answers.

The flipside of all this is that the same openness and mystery, along with the unfamiliar physique and stature of animal protagonists, does throw up significant difficulties in terms of narrative and game design. Most obviously, it can be problematic that naturalistic animal characters can’t clearly express themselves in ways we understand. This isn’t only a matter of spoken or written language, as Sutton told me. “Realistically animals can’t shrug, sigh, roll their eyes, or easily show emotions the way humans can with just body movements which definitely presents its own set of challenges in the storytelling department,” he said.

Credit: Infuse Studio

Lost Ember and Away try to avoid these pitfalls by finding ways to introduce language around their heroes. Your human soul in Lost Ember enables you to comprehend speech, and a buddy character in the form of a floating spirit narrates situations, although he doesn’t know any more than you about past events. “While he is trying to make sense of what the both of you see in the memories and the world, the player is basically left with their own thoughts,” Graff said. “This makes it difficult to explain some of the more complex details and was one of our main concerns in writing the story.” It’s a tricky balance to strike between confusing vagueness and didactic exposition.

Away’s alternative solution is to frame its events as a nature documentary. Adding commentary to its action, for Johnson, allowed the team “to explore the sugar glider’s story and follow its adventures while maintaining the game’s immersion and realism.” How exactly this works in relation to the player’s inputs, and whether the documentary voice is part of the narrative remains to be seen. But it sounds like an interesting device to explain what unfolds without intervening in the animal world itself.

One added complication is building worlds suited to the size of their characters. With Spirit of the North’s fox, for example, Sutton said the team “had trouble with keeping the scale of things correct or just the general idea that you aren’t going to be seeing things from 10 feet in the air like the third-person camera of a human.” Johnson expressed a similar challenge: “Given the sugar glider’s small size, you’re much closer to the ground than you would be in most games, making the environments surrounding you seem much larger and more detailed. We therefore had to be extremely meticulous when designing Away’s environments to make sure every plant, leaf, and blade of grass was accounted for.”

Credit: Breaking Walls

Lost Ember’s added challenge was in having all kinds of playable animal characters, from soaring birds to burrowing armadillos. As Graff told me, this “opens up a lot of possibilities to traverse the world. Especially with flying animals like parrots, but also just small animals that can fit into every nook and cranny, it’s difficult to guide the player in the right direction.” As much as the game wants to make you feel unfettered by running, flying, and swimming as different creatures, it has to ensure you can’t really break free.

Perhaps, then, we can chalk up the scarcity of animal-led games, at least in part, to the additional design challenges they present. Even this new breed seems restricted to tightly designed, high-concept indie experiences. But it’s heartening to see these attempts to place animals at the core of games because of the unique perspectives and experiences they offer. These are works that not only represent animals in a different light to most other games, but consider the connotations of being an animal in a world defined by human technology and hubris. By transporting us into the natural world, in other words, they prompt us to tell different kinds of stories about ourselves.

Header image credit: Lost Ember, Mooneye Studios

Jon Bailes is an independent games critic and researcher from the U.K. He is author of Ideology and the Virtual City: Videogames, Power Fantasies and Neoliberalism (Zero, 2019). You can follow him on Twitter @JonBailes3.