Demons are everywhere. For centuries, Christians suspected themselves to be beleaguered by armies of invisible foes lying in wait in the dark, seducing, deceiving and torturing those susceptible to Satan’s lies. It’s perhaps no surprise that demons have laid claim to the domain of video games as well and have been keeping us on our toes for decades. Anyone who spent any time playing fantasy or horror games will probably be familiar with such ominous-sounding names as Pandemonium, Abaddon, Lucifer, Azazel, Mephistopheles or Beelzebub.

Much of Christian demon lore has its roots in Jewish and Middle Eastern myth and folklore, and thus reaches back many hundreds if not thousands of years. While demons or demon-like entities play a major part in the myths of cultures all over the world, no other demonic tradition has managed to entrench itself as firmly in pop culture as that of the Judeo-Christian variety. Video games, too, have relied on this demon lore to imbue the darker aspects of their worlds with a sense of authenticity and a distant, archaic past.

While the idea of a conspiracy of devil-worshipping witches in medieval or early modern times was never been more than a paranoid fantasy, there have always been people enamored with the idea of obtaining a deeper understanding of the spirit world. This “discipline” pursued by the intellectuals of the past is called demonology, which, unsurprisingly, matured in the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, the exact historical moment leading up to the great European witch hunts of the 16th and 17th centuries. Witch-hunter manuals such as the infamous Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches) written by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger and published in 1487 contributed to the discipline of demonology. Even King James I of England (or VI of Scotland), a firm believer in the evil and threat of witchcraft, wrote a treatise called Daemonologie (1597). Demonological texts tried to make sense of the often ambiguous, contradictory and ill-defined demon lore of the past by classifying and codifying the various kinds of demons, their status vis-a-vis their divine creator, as well as the nature and extent of their powers.

Compendium rarissimum totius Artis Magicae (ca. 1775)

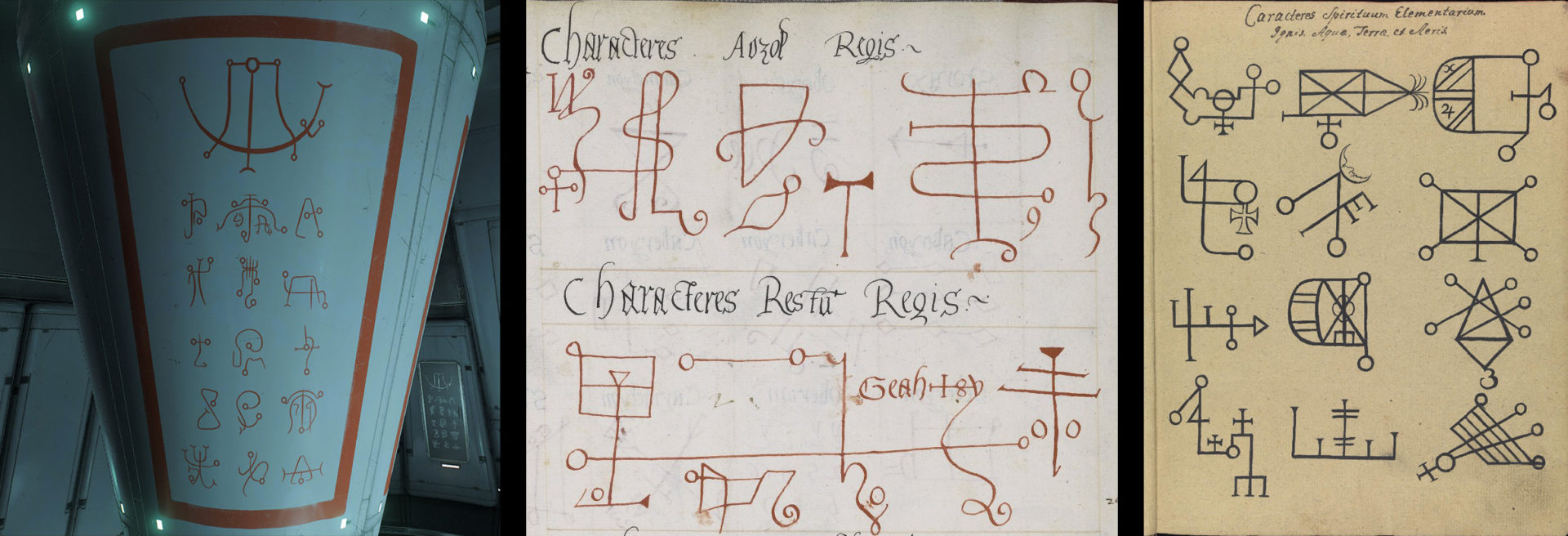

Some occultists went beyond the search for knowledge and dedicated themselves to summoning demons and forcing them to do their bidding. Unlike supposed witches, these ritual magicians didn’t pay obeisance to demons, but instead tried to subject them to their will through cleansing rituals and invoking the name and power of God. Demons, it turns out, are useful assistants for a myriad of tasks, from turning yourself invisible and foretelling the future to finding buried treasure or lost items. Even though the practice of summoning demons was, to put it mildly, frowned upon by ecclesiastical authorities, there are many surviving texts in the form of grimoires describing the hierarchies of Hell, the names of demons, their sigils, powers and how to conjure and command them. Some of these books, such as the Sworn Book of Honorius (written somewhere between the 13th and 14th century) or the Key of Solomon (14th or 15th century) are authentically medieval, though many much later works such as The Grand Grimoire also pretended to date back to medieval (or even ancient) times.

Demon lore seeped into countless stories and literary works such as Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (ca. 1592) or John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), keeping it alive well into the Age of Enlightenment and beyond. That same demon lore has since found a foothold in popular culture: horror movies, anime, pen and paper RPGs, comic books, heavy metal lyrics. From there, it sunk its claws into video games and shows no signs of letting go.

Most games get at least some demon lore right. Take 2016’s Doom and the demonic sigils that decorate many of the game’s surfaces. These sigils are inspired by medieval and early modern grimoires such as the famous 17th century book of spells The Lesser Key of Solomon (or more precisely its first section, “Ars Goetia”) and were used to summon the demon associated with a particular sigil. The idea that Doom’s demons are ranked in a kind of feudal hierarchy, with enemy types called “Hell Knight” or “Baron of Hell,” also mirrors old ideas about the “social” order of Hell, in which lesser demons were thought to be governed and led into battle by mighty dukes and kings of Hell. We all know from games like Diablo II and its soulstones that certain objects can bind, control, or even trap demons within them. The Seal of Solomon, a signet ring given to King Solomon by the archangel Michael in the non-canonical Testament of Solomon, was said to have been used by the king to force demons to build his temple. And in a posthumous trial in the early 14th century, none other than Pope Boniface VIII was accused of, among other things, possessing a ring containing a demon advisor.

Certain demons mentioned in historical sources have attained real celebrity status and rear their ugly heads in more than one game. One of them is Asmodeus, who is variously also called Asmoday or Ashmedai. His name is believed to have derived from the Iranian spirit Aeshma-daeva, literally “wrath-demon.” According to both Johann Weyer’s Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (1577) and the “Ars Goetia” (from which Weyer copied), Asmodeus is a “great king” of Hell, “strong and powerful” and commanding 72 legions of lesser demons. He is endowed not with one, but three heads: one like a bull, one like a man, and one like a ram. He appears “with a serpent’s tail, belching or vomiting up flames of fire out of his mouth his feet are webbed like a goose, he sitteth on an infernal dragon carrying a lance and a flag in his hands.” The “exorcist” (as the magician is called) who summons Asmodeus must call the demon by his name in order to subdue and command him: “Thou art Asmoday, and he will not deny it; and by and by he will bow down to the ground.” He then provides the magician with the so-called “ring of virtues” and “teacheth the art of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and all handicrafts absolutely; he giveth full & true answers to your demands, he maketh a man invisible, he showeth the place where treasures layeth, and guardeth it.”1

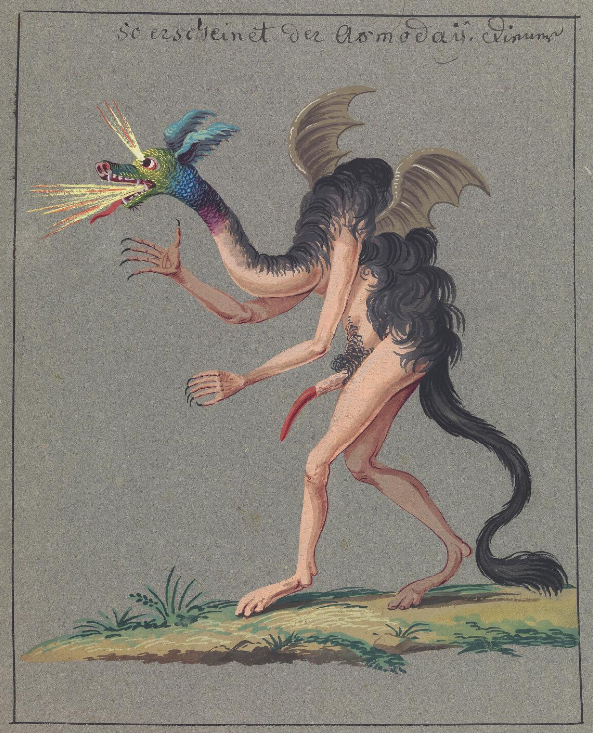

Compendium rarissimum totius Artis Magicae

This helpful creature has often been associated with lust and lechery. In the Testament of Solomon, one of the demons commanded by King Solomon is Asmodeus, who responds to Solomon’s questions: “I am called Asmodeus among mortals, and my business is to plot against the newly wedded, so that they may not know one another. And I sever them utterly by many calamities, and I waste away the beauty of virgin women, and estrange their hearts… I transport men into fits of madness and desire, when they have wives of their own, so that they leave them, and go off by night and day to others that belong to other men; with the result that they commit sin, and fall into murderous deeds.”2

The Malleus Maleficarum agrees with the assessment of Asmodeus as a demon of lust and adultery: “But the very devil of Fornication, and the chief of that abomination, is called Asmodeus, which means the Creature of Judgement: for because of this kind of sin a terrible judgement was executed upon Sodom.”3 In one striking illustration of an 18th century grimoire, Asmodeus appears in a very different form, but certain exaggerated features on full display make it hard to miss his sexual connotations.

Asmodeus makes an appearance in quite a few games, and some of his historical associations have survived the transition in some form or other. In Persona 5, he manifests as the Shadow form of Suguru Kamoshida, a coach, bully and serial sexual harasser of his female students. His visual design not only betrays unchecked lust, but also overbearing ambition and greed: Asmodeus as Kamoshida’s shadow self is a naked, pink giant with leering, unfocused eyes and a giant, drooling tongue, holding golden eating utensils and a glass of wine, symbols of both greed and gluttony (a sin arguably related to lust). In front of him, between his legs, stands the “Trophy of Obsession,” a golden loving cup filled with nude, struggling bodies. Interestingly, he’s also sporting a set of ram’s horns and wearing a crown reminiscent of Asmodeus’ illustration in Jacques Collin de Plancy’s famous Dictionnaire Infernal (1863).

In Asmodeus’ most recent role in Night School Studio’s Afterparty, he takes on a much less grotesque form. Here, too, he is described as one of the monarchs of Hell, but he’s given to immoderate partying rather than reigning. Wrapped in Christmas lights and strips of cloth that barely conceal his physique and topped off with a huge sombrero, he doesn’t exactly strike an imposing figure. Indeed, he’s a rather pathetic character, attempting to distract himself from the fact that his wife left him through non-stop dancing and drinking. Throughout the game, he is never spoken of as a demon of lust, but his representation gives an ironic twist to his historical associations: As it turns out, Asmodeus isn’t just good at wrecking the marriages of hapless humans, but his own as well.

In Diablo III, Asmodeus appears in thin disguise as Azmodan. (Who does he think he’s fooling?) Here, he is simply known as Lord of Sin. We may have to strain a little bit to see possible ties to other representations, but if we look at his concept art, a few characteristics have obvious parallels. For one, he is massively obese, possibly linking him to the “sin” of gluttony, not unlike Kamoshida in Persona 5. He’s also adorned with golden and ostentatious pieces of jewelry that highlight his material greed and arrogance. If we stretch our interpretation a bit more, his kinky nipple piercings and suggestively shaped “vagina dentata” mouth could also hint at his threatening sexuality.

Asmodeus also appears in Daniel Mullins’ Pony Island, this time as a sentient and malevolent computer program named asmodeus.exe. While neither his appearance nor his character has much in common with other interpretations (apart from the crown he seems to be wearing), there are a couple of noteworthy moments in our confrontation with asmodeus.exe. For one, he commands us to say (or rather type) his name. In the “Ars Goetia,” the exorcist establishes authority over Asmodeus by speaking his name. In Pony Island, the dynamic is reversed: By forcing us to type his name, Asmodeus demonstrates his dominance over us. It’s a rare game in which demons rely on tricks and deception rather than brute force. Pony Island’s asmodeus.exe enjoys playing games with us, using clever misdirection and illusions to disorient and disconcert.

Another prominent demon in gaming is Baal (also sometimes spelled Bael or Bhaal). Ba’al, simply meaning “Lord,” was a title used for various important gods in the ancient Middle East. The same title can also be seen in the names of several other demons, such as Beelzebub (originally Ba’al Zebub, i.e., “Lord of the Flies”), Balberith (Ba’al Berith) and Belphegor (Ba’al Pe’or). Like the Canaanite deity Moloch, Baal was reinterpreted by Judeo-Christian monotheism as a demon leading mankind astray, away from the “one true God” and into inadvertent demon-worship.

In Weyer’s Pseudomonarchia and the “Ars Goetia,” Baal or Bael is described not only as a king of Hell, but also as “first principal spirit.” Even though he supposedly rules over 66 legions of demons, he does not appear like the martial type: “He appeareth in diverse shapes, sometimes like a cat, sometimes like a toad, sometimes like a man, and sometimes in all these forms at once. He speaketh very hoarsely.”1 If properly summoned, Baal will grant the magician wisdom and invisibility. Baal, then, is a shapeshifting, cunning creature in the guise of animals long associated with black magic and witchcraft.

In the Baldur’s Gate series, Bhaal features as “God of Murder,” a being that has little in common with historical demon lore apart from his deviousness and evil intent. In Diablo II, Baal is a central figure in the story, and finally our main antagonist (and title character) in the game’s expansion, Lord of Destruction. The expansion’s opening sequence shows Baal at the helm of his army, making his enemies explode with dark magic. But neither does he lack the more subtle and devious qualities ascribed to him by demonological texts. In Diablo II’s cutscenes, Baal plays the role of a deceiver and shapeshifter with a malevolently playful streak; he approaches Marius, the drifter who narrates the game, in human disguise and pretending to be the angel Tyrael. He manipulates Marius into handing over the soulstone fragment, before finally mocking and killing him. In Baal’s “true” form, his most striking feature is the spider-like legs emerging from his back. His spidery look highlights his deviousness, but there may be more to it: In the illustrations of the Dictionnaire Infernal, Baal (or Bael) is interpreted as three heads (man, cat and toad) on a body carried by spider legs.

Interestingly, this illustration seems to have been a major inspiration for depictions of Baal in Japanese games. In the first Shin Megami Tensei, Bael appears just like he does in the Dictionnaire Infernal, as three heads on a spider’s body. In Shin Megami Tensei 2, he’s seen as a naked man wearing nothing but a crown and spider-adorned arm rings, riding a large toad and carrying a black cat on his shoulders; his shape has changed, but the iconography has remained intact. Bael is also the final boss of Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, where he attacks as three giant heads in the form of (you guessed it) a black cat, a toad, and a demonic man. In both Bayonetta 2 and Devil May Cry 4, Baal takes on the form of a giant, predatory toad.

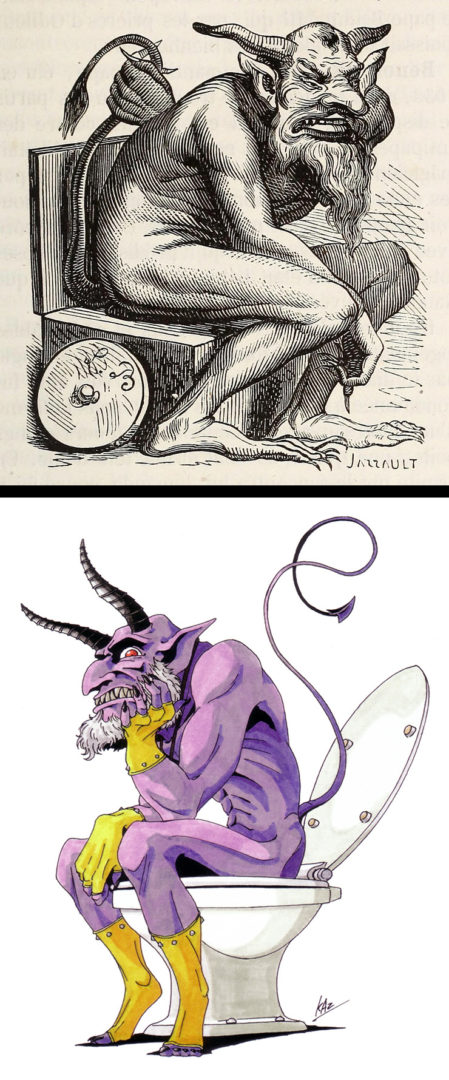

The Shin Megami Tensei series and its spin-offs have been strongly influenced by Western artistic depictions of demons in general, featuring dozens of “real” demons, including fairly obscure ones such as Orobas, Forneus, Nebiros, Andras, and Flauros. The influence of the Dictionnaire Infernal’s illustrations can clearly be seen in some of them, such as the owl demon Andras, the giant fly Beelzebub, the upright horse Orobas, or my personal favorite, the grumpy toilet demon Belphegor, “Ambassador of Filth.”

and Shin Megami Tensei.

Shin Megami Tensei’s rendition of Baphomet, aka the Sabbatic Goat, the demon or dark deity the Knights Templar had been accused of venerating in the 14th century, closely resembles Éliphas Lévi’s familiar 19th century image. The iconography of SMT’s Lilith, demoness and first woman according to Jewish folklore, seems to have taken strong cues from John Collier’s 1887 sexually charged painting of Lilith with a snake coiled around her, an interpretation that could hardly be more different from Lilith’s androgynous and terrifying appearance in the recent Diablo 4 trailer.

From medieval and early modern grimoires and demonological treatises, over a 19th century “infernal dictionary,” to today’s pop culture and video games, examples like these show how persistent historical demon lore can be and how games continue to keep alive centuries-old iconography and ideas. But these examples also illustrate just how malleable and inconsistent our visions of demonic entities often are. Their names, shapes and characters morph and shift with each appearance, so much so that it makes little sense to speak of demons like “Baal” as individual, distinct entities. Rather, their names evoke a loose mingling of associations in constant flux. Where does one demon end and another begin? One of Shin Megami Tensei’s demons, Belberith, captures this fluidity by appearing as a blob merging the features of various other demons, such as Bael and Belphegor. It is in the nature of any demon to defy even the most diligent and long-standing attempts at codification and, given the right conditions in the melting pot of popular imagination, to grow, diversify, and finally, perhaps, become Legion.

It’s no coincidence that some demon names such as Beelzebub have often been used as synonyms for Satan himself, as if individual demons were nothing but facets of the devil. In extreme cases, there remains nothing but vague sound patterns. Take the Daedric Princes of Elder Scrolls lore, where familiar demon names are reconfigured into new names that still carry demonic associations. Molag Bal, “Prince of domination and spiritual enslavement,” has little to do with either Moloch or Baal, but still evokes a sense of infernal threat and malevolence. Mephala, “Prince of unknown plots and obfuscation,” also sounds as if the names of two demons, Malphas and Mephistopheles, had been smashed together in a car crash.

This malleability is only fitting, since demons notoriously refuse to be pinned down by human understanding; demons have always been portrayed as elusive deceivers, liars and shapeshifters. And it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the descriptions, stories, and artistic renditions of the past, too, were full of contradictions and changed massively with time and cultural contexts. One only needs to look at the long history of Satan, aka Lucifer, aka the Devil, to see this. In many illustrations of Hell and the Last Judgement, Satan appears as an enormous beast gorging himself on the bodies of sinners by the handful. In the book of Revelations, he manifests as a seven-headed dragon. In John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Satan transforms himself into the famous snake that tempted Eve. In early modern accounts of witchcraft, the devil approaches mortals in the guise of a man or an animal, such as a goat, a dog, or a cat. Finally, there’s the image of Lucifer as a fallen angel who still retains some of his beauty and grace. This clash between pathos and beauty on one extreme and cruel beastlinesson the other is humorously and succinctly illustrated in Afterparty: Upon entering Satan’s office, we see a statue of a radiant angel on the left, and a statue of a multi-headed, man-eating beast on the right. This duality is also obvious in some of SMT’s interpretations of Lucifer as a horned angel.

It’s a shame that most games fail to capture the full multiplicity of the demonic. Demons have become a staple of fantasy games, little more than an expected enemy type serving as ready-made, cookie-cutter villains. They serve as an excuse for cartoonish grotesqueries and deformity, and while there’s nothing wrong with that, they often lack both the genuine horror as well as the sheer outlandishness of some historical descriptions and depictions of demons. Hellish paintings by late medieval artists such as Hieronymus Bosch or Jan van Eyck, as well as some illustrations from grimoires, should be enough to show how much creative potential and sources of demonic inspiration are still locked away in the lower levels of Hell, available to those lost souls who are ready to descend deep enough.

1. Quoted from Reginald Scot’s 1584 translation of the Pseudomonarchia, published in his Discoverie of Witchcraft.

2. F.C. Conybear’s 1898 translation.

3. Montague Summers’ 1928 translation [PDF].

Header image credit: Diablo Immortal art, Blizzard Entertainment

Andreas Inderwildi is a writer, would-be novelist and freelance game critic who has written features for Eurogamer, Rock Paper Shotgun, Edge, Kotaku UK and others (far too many of which about Dark Souls and Bloodborne). He loves all things strange and morbid and spends a lot of time thinking and writing about the Middle Ages, folklore, horror and the occult. Sometimes tweets @mashxtomuse.