Since the advent of open-world games at the turn of the century, developers have endeavored to craft impressive digital representations of the world’s most iconic structures and cities. From the cracked asphalt jungle of Grand Theft Auto IV’s ersatz New York City to the crumbling marble monuments of The Division 2’s Washington, D.C., the triple-A side of the industry is well on its way to capturing every major U.S. metropolis in bits and bytes by the time the oceans rise to claim them.

Yet when it came to the highly anticipated Dreamcast adventure game Shenmue, which arguably pioneered the idea of a living, breathing “open-world,” creator Yu Suzuki wasn’t interested in building a fictionalized reproduction of Tokyo’s “Shibuya Scramble,” or a monument to its infamous pleasure district, Kabukicho. Instead, Suzuki chose the quiet port town of Yokosuka as the setting for the first chapter of his tale of kung fu and sailors, bringing a level of unprecedented realism and granularity to the town’s Dobuita Street and its environs—and immortalizing an obscure stretch of road, perhaps unwittingly.

Credit: Kentagon via CC BY-SA 4.0

In recent years, with the much-deserved crossover success of Persona 5’s love letter to Tokyo and the Yakuza franchise’s Kamurocho (a Disneylandified take on Kabukicho and my personal pick for the best video game locale of all time), curious Westerners can get their digital tourism fix without ever having to leave the comfort of their couch. But for superfans of Yu Suzuki’s famously incomplete series, visiting the real-life Yokosuka has become a popular activity, a rite-of-passage that some have dubbed the first stop on their “Shenmue pilgrimage.”

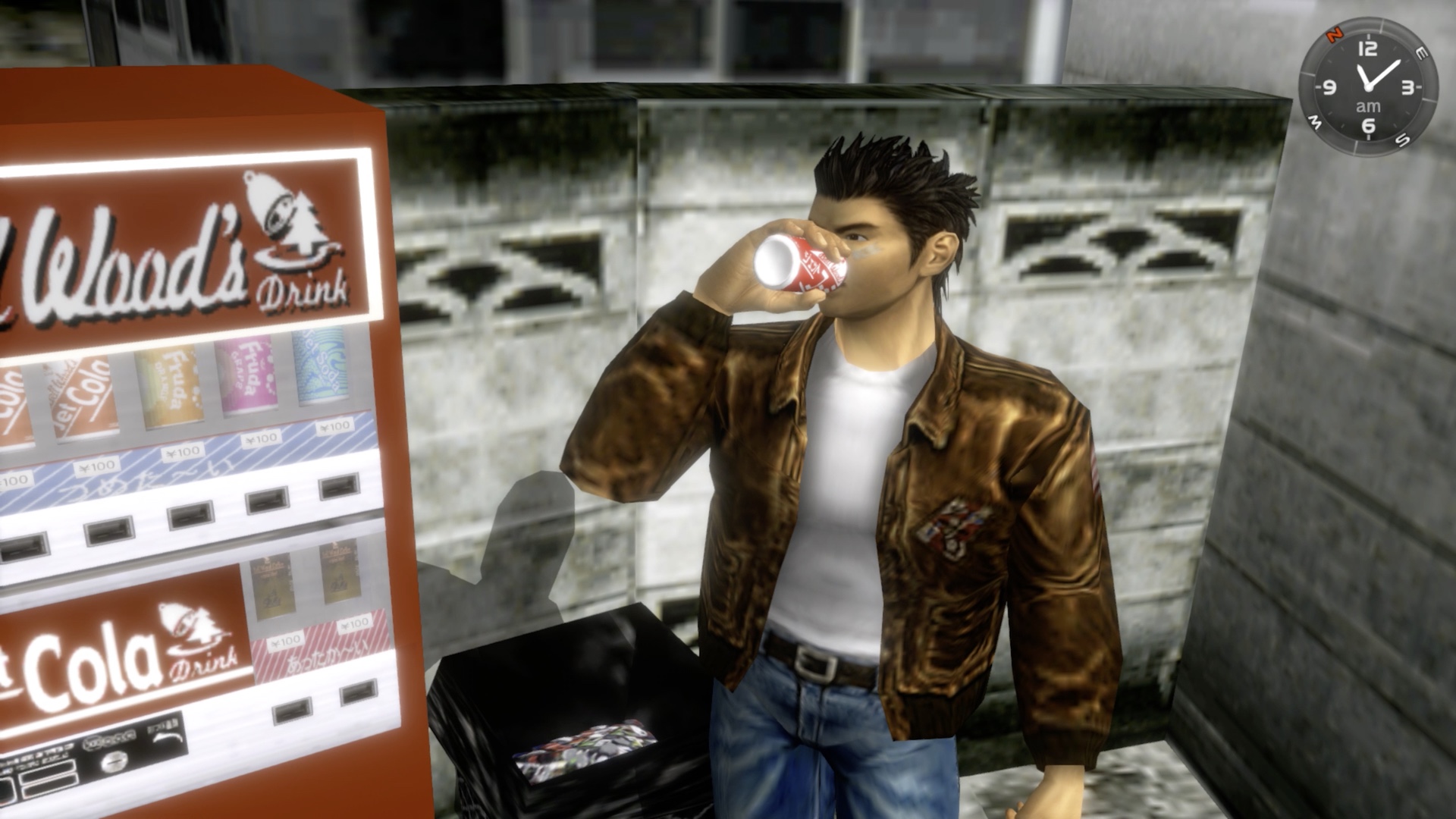

Today, the original Shenmue is known mostly as an artifact of a bygone era, even with the long-awaited release of its third installment last month (to mixed reviews, some of which knocked the game for feeling dated). Shenmue is a white elephant of a console exclusive that remains one of the most expensive games ever made. Though publisher Sega clearly hoped that the series would pierce the veil of mainstream success, the uncompromising purity of Suzuki’s vision produced an experience that baffled many players. True to its sleepy suburban setting, with its stiff dialog, methodical pace, and hours upon hours of wandering around hunting for the next cutscene, the first-half of Shenmue 1 in particular is a monument to mundanity. But while this commitment to the quotidian reality of 1986 Japan turned off typical gamers in droves, some players found its unique premise compelling—perhaps even irresistible.

Credit: Sega

“The thing is, when you’re playing some big RPG, there will be some text explaining where the main guy is from, what his basic backstory is, and then you move on,” said Adam Koralik, a YouTuber who often posts Shenmue content to his channel. “Shenmue [1] is that prologue, and I don’t think people really appreciated that at the time. It’s the text that says, ‘This is your background, this is your home,’ and by the time you get all the way through it, you don’t feel strange there anymore. But when you [arrive in Hong Kong] in [Shenmue] 2, you’re the gaijin, you’re the weirdo. Yokosuka isn’t just some random spot where the game happens to take place. For some fans who played the game, playing Shenmue wasn’t just a video game, it was something they embraced, like, ‘[Ryo’s] life is my life now.’ For them, it feels like home.”

Though Koralik describes himself as an avowed “superfan” of the franchise, when he first played Shenmue back in 2000, he didn’t quite understand its niche appeal. A few years later, during a long, aimless trip to New Jersey, a friend managed to convince Koralik to give the game another look, and the two of them became totally immersed in Ryo Hazuki’s quest for revenge. Even still, when Koralik finally visited the real-life Dobuita Street for the first time, it was the result of happenstance, not a dedicated journey. “I was visiting Japan for another event, and I got my hotel information, and it said New Hotel Yokosuka,” he explained. “I was like, wait, the Yokosuka? A couple of days go by, and I’m hanging with a buddy near there, and I told him, ‘You know, it would be great to see Dobuita Street, that’s where Shenmue takes place.’ And he just laughed and said, ‘Oh, yeah? Because you’re standing on it.’ I was just blown away. I was overwhelmed, being in what should be the Mecca for Shenmue fans, and he just said, ‘You fucking nerd.’ It was really funny.”

Koralik has since visited Yokosuka four times since he first unconsciously tread on its holy ground, but he says it’s only now that he’s beginning to understand why Suzuki chose to set one of the most ambitious games of all time in such a little-known area. In Japan, Yokosuka is arguably best-known as the site of a U.S. naval base that brings in a steady stream of foreign sailors and tourists. As Koralik sees it, because of this influence, Yokosuka almost feels like a Westerner’s idea of what a Japanese town feels like, like the constructed facade of a theme park. According to fellow Shenmue tourist James Reiner, who has also travelled all around Japan, American food abounds all up and down the block; it’s much easier to find a burger or a taco there than in other parts of the country. “Last time I was there, I decided to get the Trump burger,” he joked. “It’s awful. It had peanut butter on it for some reason.”

Like Koralik, Reiner first played Shenmue as a teen, and very quickly became entranced by what he describes as its “mystical” atmosphere. However, while he himself viewed the Shenmue pilgrimage as a “lifetime goal,” he had to scrimp and save to shoulder the considerable cost of such a trip, since the plane ticket to Narita Airport from New York alone ran him almost $1,000. “I would definitely say that if you wanted to go all out, you should plan on around $300 a day,” he said. “Maybe you could do it for less, but my thought is, if you’re there, you might as well do everything there is. If you want one of the jackets, like Ryo wears, that’s going to run you up to $700 alone, so be prepared.”

influenced the city’s more Westernized elements.

As far as the actual attractions, the fans say that the area hasn’t actually altered that much since the game’s 1986 setting. There’s a watering hole called Tom and Jack that likely served as the model for the bars that Ryo raids during his infamous search for sailors; several fans also noted that it might’ve inspired the name of a character named Tom, who owns a hot dog stand. To Koralik and Reiner, the shop that most resembles its Shenmue equivalent is a jacket shop called Mikasa Vol. 2—the owner even correctly identified them as fans of the series. According to another fan who goes by “Switch” and runs the blog Phantom River Stone, perhaps the best Shenmue resource on the web, a motorcycle shop once stood in the neighborhood, just like in the game. Today, it’s a candy store. Last year, Sega ran a promotional campaign where they set up standees all throughout the area, and distributed fliers and maps to show people how the locations in the game correspond to real-life geography.

Though these businesses might sound a bit underwhelming to those who weren’t waiting on Ryo’s third adventure with bated breath for 20 years, the fans agree that the mundanity is part of the appeal. “I think it was my third time there that I realized, ‘Yeah, this is just a normal place where people live.’ But I think that’s why it works so well,” Koralik said. “That’s how it can feel like home to so many different people.”

“When I got off the train the first time, I had to stop recording, because I was just bawling my eyes out,” Reiner said. “It really did feel like I was coming home… I found a parking lot and recorded myself doing some goofy kung fu [like Ryo does in the game]. In the beta version of Shenmue, there are some stairs in the area Yamanose that go down to where Ryo’s friend Yojiro lives. In the final game, they’re a little different, but I found the beta version of those stairs in real-life. I was just so amazed with myself, like, wow, nobody would notice this. This is the hardcore shit, man.”

Credit: MIKI Yoshihito via CC BY 2.0

In the coming years, Reiner plans to make the complete “pilgrimage,” which involves visiting Hong Kong and several villages in rural China. Though he admits that the cost will be steep, and the process of obtaining a Chinese travel visa might prove somewhat onerous, he’s ready to make the trek as soon as he has the necessary finances in order. “It’s just something that’s important to me,” he said.

While cases of exploring the real-life spaces that video games draw inspiration from are far from well-documented, even today, there are other examples from across the world of art. For example, Bloomsday is a nearly-century old celebration of the works of James Joyce, in particular his novel Ulysses, which famously takes place in a single day.

According to Carlos Ramírez, a writer and academic who wrote a book on Shenmue back in 2015, this Yokosuka tourism is a unique case that represents the idiosyncratic nature of the game itself. “It’s the only case I know of where the city represented gained tourist relevance after it,” he said.

“Of course, there are people who travel to Italy after playing Assassin’s Creed, but it’s not the same phenomenon. These spaces don’t become places of devotion in such a natural way. There’s a certain process of ‘appropriation’ of the real space (Yokosuka) by the fans—due precisely to their lack of tourist relevance—that allows them to carry out a series of rituals associated with fan pilgrimage… This phenomenon, quite documented in the case of anime, hasn’t been studied enough in the field of game studies, perhaps partly because there are hardly any cases as evident as that of Shenmue and Yokosuka.”

Header image credit: Sega

Steven T. Wright is a reporter and novelist living in the Twin Cities. He is the former independent games columnist for Variety, and he has written for Rolling Stone, Polygon, Vice, and many others. He almost named his novel after a city in Final Fantasy, but his friends talked him out of it.