The Outer Worlds is an elephant.

As anyone who played 2010’s Fallout: New Vegas can attest, Obsidian Entertainment is among the best in the business when it comes to building role-playing games that truly live up to the name of the genre. In the most successful Obsidian RPGs, the choices you make toward building out your character feel meaningful in a way that goes beyond simply doing more damage with a certain type of weapon. Your stats and skills can have a substantial impact on how the story or individual missions unfold, opening up alternative pathways that adapt to what your character does well rather than merely funneling you into the same confrontations at every beat. Like the best tabletop DM, the studio tries to anticipate what a certain type of player—say, a silver-tongued pacifist or a stealthy, sociopathic sniper—might look for in a game and build a design that accommodates it naturally. This particular flavor of Obsidian role-playing is alive and well in The Outer Worlds.

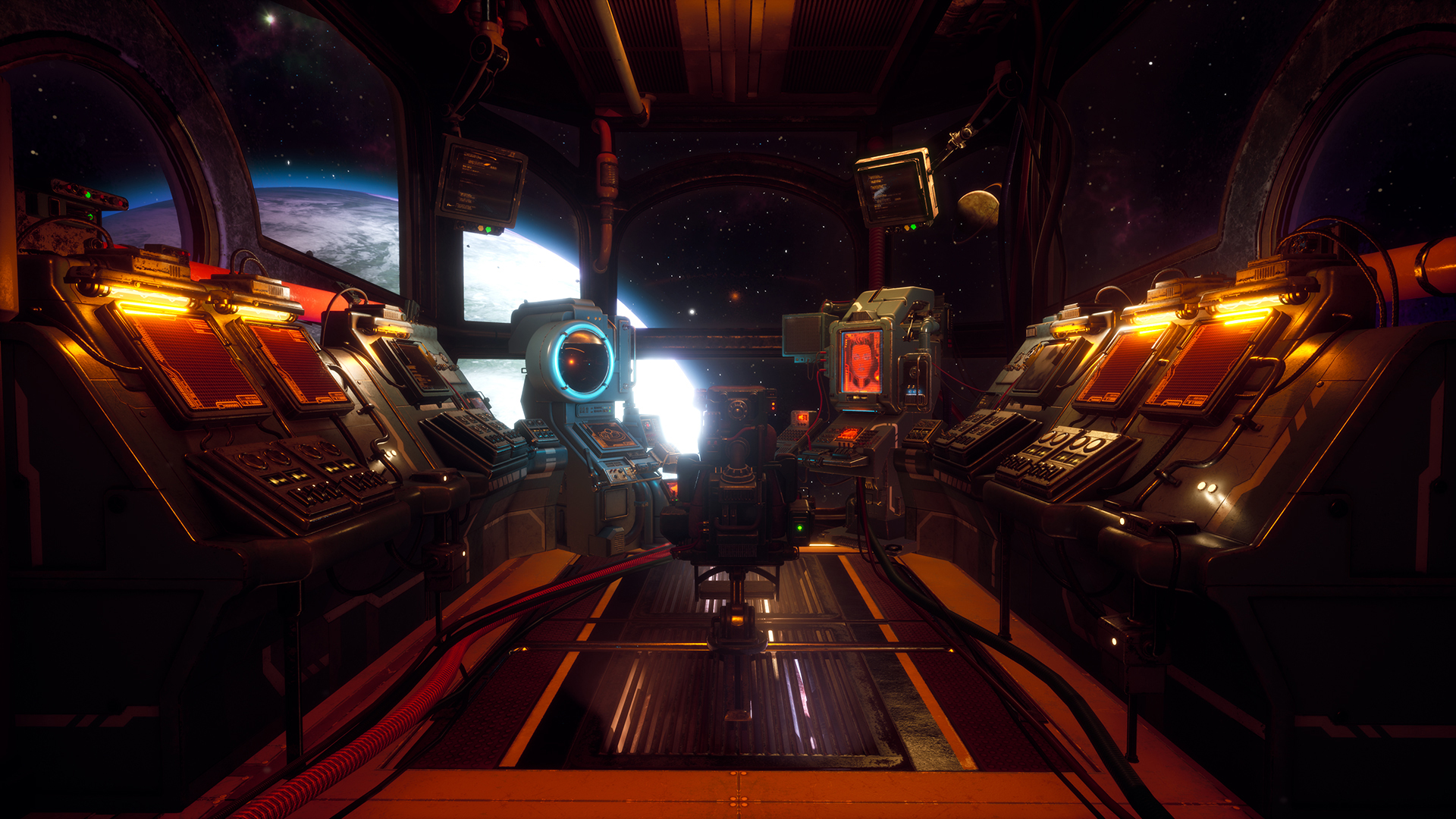

Set in a distant future where corporations have obtained near total control over society, The Outer Worlds sends you to the Halcyon Colony, a series of colonized worlds lightyears from Earth. Your character was originally meant to arrive as part of a second wave of colonists before your ship, the Hope, went missing, leaving all its inhabitants frozen in suspended animation. Your rescue, as outlined in an amusing character creation process, comes at the hands of a mad scientist named Phineas Welles, who’s probably a genius and definitely eager to take on the Board of corporations that run Halcyon.

Credit: Private Division.

In truth, it’s difficult to discuss The Outer Worlds without mentioning New Vegas. Obsidian seems to have taken great lengths to build the closest spiritual successor they could without risking the ire of Bethesda’s legal team. While there’s plenty that’s new or different—not least of which is the fact that the game takes place across a number of smaller open-world maps on different planets, rather than one big one—the core experience of playing the game feels familiar. In many respects, this is a beefed-up take on Obsidian’s last foray into Fallout: combat with both guns and melee weapons; branching conversations that sometimes open up alternate paths through the story; exploration with plenty of sidequests to discover; companions to recruit to your party; and a main quest that drops you in the middle of a dispute between two factions, forced to decide the fate of the local population. One can hardly fault the studio for this, given the number of petitions we’ve seen for a New Vegas sequel and the outsized response to the unfounded rumors it was working on one.

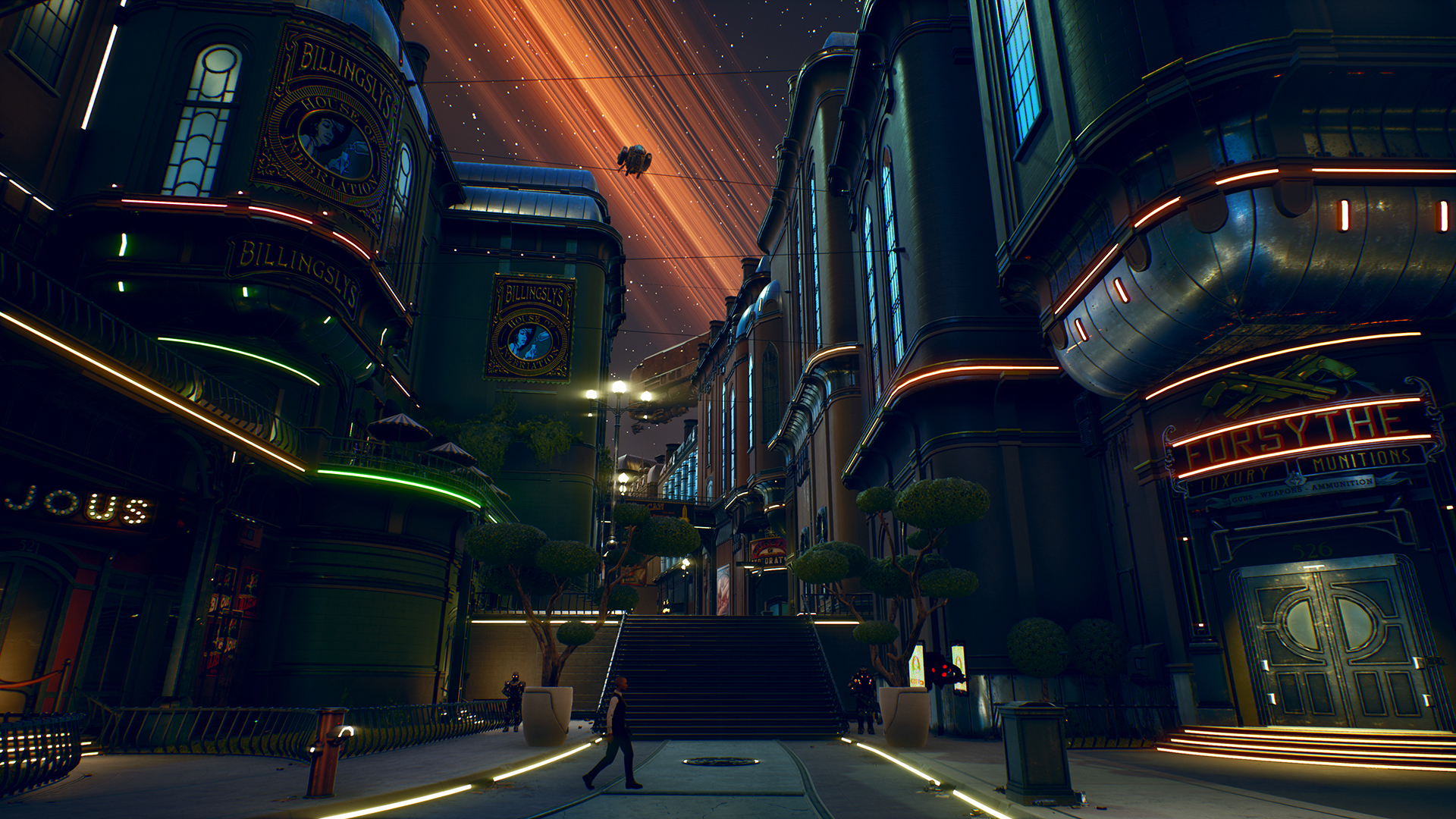

What’s remarkable, however, is that The Outer Worlds never feels like a knockoff. Yes, conversations and combat and some of the gameplay systems are familiar, but additions like a time-limited disguise system to help avoid combat in certain areas and Tactical Time Dilation—a recharging bullet-time ability that lets you target certain body parts to deal additional damage or status effects—give portions of the game a distinct enough feel. More importantly, the world of Halcyon is just as well-realized as any setting in the Fallout canon. Borrowing broadly from a pre–World War II aesthetic, the settlements, gear, and wildlife all feel like the byproduct of a single universe, united by a visual consistency. The writing conveys a real sense of culture, full of special lingo and class distinctions and history. So many of gaming’s science fiction worlds come off as overly derivative or bland. The Outer Worlds, despite taking some obvious cues from Firefly and Fallout, is anything but.

And of course, New Vegas’s excellent sense of humor carries over, too, both in dialogue and in gameplay. This is still a game where you’ll sometimes have to strip naked and drink a bunch of coffee so you can pick a lock successfully. And the extra dialogue options you get if your character’s intelligence is low are often hysterical (if a bit inconsistent in the degree of stupidity).

Credit: Private Division

But we’re back to the pachyderm in the room. There’s an Indian parable, dating back thousands of years, about a group of blind men who encounter an elephant. Each of the men touches a different part of the animal, and each comes away convinced he knows exactly what this object is. The man who feels the elephant’s trunk says it’s a snake, the one who feels the leg says a tree trunk, the one who feels the tail says a rope. The man who touches the elephant’s butt doesn’t say anything; it’s a secret he takes to his grave.

Point being, I’m a blind man. The Outer Worlds is an elephant.

Short of pouring in 12 more playthroughs and delaying this review by months, I couldn’t possibly claim to understand everything about what you can experience in the game. The length is perhaps a bit shorter than other games of this sort—my initial playthrough took me close to 50 hours, but I completed all of the side content I could find and explored pretty thoroughly—but the design density across that shorter running time complicates things considerably. You can stick with Welles for the entire story, or sell him out to the Board the first chance you can get. You can swap allegiances midway through and double and triple-cross factions to the point you’re not even sure where your own allegiances lie. Some of the ancillary questlines offer just as much branching, with the best calling to mind the most memorable side stories from the Fallout series, like Fallout 3’s Megaton, only with an even greater depth. And nearly everything you do will be reflected to some extent in the game’s ending, which recaps the fates of just about every major player in a narrated slideshow.

I did mess around with alternate save files so I could see a bit more of the elephant, and I’ll admit that the game isn’t always perfectly reactive. If I killed a faction leader at one point in the questline, I could immediately inform the rival leader that I’d done so and progress from there. But when I tried killing her at a different beat, the game didn’t offer me any new dialogue options at all. I could still complete the quest, but it took a while before anyone acknowledged my decision. Still, that was the sole example I found among the dozens of little experiments I ran, and much of the rest of what I saw had shockingly granular reactions to my decisions. In one instance, I thought I’d discovered a bug: I could kill a character close to one of my companions, and the moment I tried to speak to said companion she’d immediately leave the party—but if I never started that conversation, she’d stick around and even follow me into battle. I finished the game in both states, and was surprised to discover the game could tell the difference between those two states, and gave slightly different endings for the character in each case.

Credit: Private Division

But the story isn’t even the most dramatic thing that changes between playthroughs. There are so many different gameplay elements locked behind different skills that it’s truly impossible to see everything in a single playthrough. Because I focused almost completely on turning my first character—intergalactic dirt farmer Mud Chamberlain—into a dumb, hammer-weilding tank, I ended up locked out of entire swaths of gameplay. I never unlocked special attacks for my companions. I never experimented with mixing different drug cocktails in the inhaler you use to heal in combat. I never got to hack robot enemies or intimidate humans during combat with superior dialogue skills. I dabbled in ranged combat, but I couldn’t tell you how it feels to be the deadliest gunslinger the game’s ruleset allows. I only briefly experienced the ability to upgrade weapons by “tinkering” using the science ability. I wanted Mud to be great at hitting things hard without thinking, and there were meaningful consequences for that decision.

What’s remarkable is how rarely during my playthrough I felt like I was being outright punished for my approach. Sure, a handful of times I found myself wishing I could lockpick a door or smooth talk my way out of conflict, but those situations, in hindsight, made perfect sense for my character and her trajectory, and there was always an alternate progression that felt satisfying in its own right.

What’s more, melee combat feels much deeper than most role-playing games, which tend to rely on merely reducing the damage you take and upping the amount you deal to let you button-mash your way through battles. While The Outer Worlds is hardly Sekiro, the addition of a dedicated block button and bonuses when you time it perfectly make battles against melee enemies more engaging, while a dodge ability that lets you evade incoming fire and quickly close the distance makes taking on ranged foes just as involved. Add in Tactical Time Dilation for when you need to do a little extra damage or target a specific body part, and you have real options beyond simply hammering the trigger. Early on, I worried that bashing skulls would get old long before the credits rolled, but thanks to the real sense of progression offered by the melee-centric skills and unlocks, it never did.

Credit: Private Division

I suspect given the complexity of all the interlocking systems here that the game may prove to be hilariously unbalanced in one direction or another. In fact, given my own experience, I strongly suspect it. Near the very end of my playthrough, I used the respec machine onboard my ship, the Unreliable, to swap all my skill points so I could upgrade my favorite science weapon, the Prismatic Hammer, for relatively cheap, and then I swapped back to my bruiser build. (You’re technically free to respec as much as you want, but the price doubles each time, so you’ll want to use the feature sparingly.) My damage before had been around 500 points per attack. After about two minutes of work and few thousand bits, I bumped it up to over 10,000 a swing. I dropped the final boss in two hits.

Despite being a little underwhelming, though, my moment of triumph didn’t feel cheap. I felt like I’d earned that anticlimax by reaching the level cap without abusing the respec, and by learning just enough about the systems to maximize my character build. If I “broke” the game, it was because I took dozens of hours solving the mystery of how. I also strongly suspect I wouldn’t have such an easy time pulling the same stunt on the blisteringly hard Supernova mode, which adds requirements for eating and drinking, save restrictions, and permadeath for companions. I dipped my toes in briefly before starting the review and died during the tutorial, which pretty much told me what I needed to know.

The thing is, I’m a bit more hesitant than usual to assume that any given playthrough of The Outer Worlds will be as satisfying as mine. Maybe the gameplay elements I didn’t touch and those I only lightly grazed are boring or busted. Maybe most of the possible character builds or paths through the story suck. Maybe, through dumb luck, I’ve discovered being a hammer-swinging moron berzerker with a heart of gold is the absolute pinncale of what the game has to offer. Maybe The Outer Worlds is just a really good snake.

But I think it’s an elephant.

Header image credit: Private Division

|

★★★★★

The Outer Worlds is an impressive spiritual successor to Obsidian’s work on Fallout: New Vegas, mixing familiar design elements and the same zany attitude with an imaginative new universe and even deeper role-playing. While you can breeze through the main questline a bit quicker than in similar games, this is the sort of RPG experience you’ll want to play through multiple times, with multiple builds, to see all the systems and narrative paths on offer. |

Developer Obsidian Entertainment Publisher Private Division ESRB M - Mature Release Date 10.25.2019 |

| The Outer Worlds is available on PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and PC. Primary version played was for PS4 Pro. Product was provided by Private Division for the benefit of this coverage. EGM reviews on a scale of one to five stars. | |