The most potent image of the Hundred Years’ War is the chevauchée. As employed by the English during the conflict’s opening phases, the chevauchée was a kind of brutal raid aimed at inflicting misery on the French people, forcing military confrontation by terrorizing its population with slaughter and destruction. More than the great battles, immortalized in monuments and Shakespeare, of Agincourt and Crécy—or the romanticized legends grown up around the bloodthirsty Henry V and doomed patriot Joan of Arc—it’s the nightmare faced by French noncombatants swept up in the War’s more than century of battles that speaks to the reality of the era for so many who lived through it.

Asobo Studio’s A Plague Tale: Innocence is a game meant to communicate that aspect of the past, largely forgoing renowned names and events for a smaller-scale story of the period. Its story is set in the late autumn of 1348 and the early winter of 1349, just over a decade into the Hundred Years’ War, during a period in which England had won numerous victories on the back of King Edward III’s chevauchée campaign. Though an uneasy truce temporarily—and weakly—diminished full-scale hostilities during this time, the country was still devastated by years of carnage. Notably for A Plague Tale, the Black Death had also begun to spread across Europe.

The game’s protagonist, a teenaged noble named Amicia de Rune, begins the story seemingly isolated from the War, living in the comfort of an idyllic château in rural Guyenne, an area that now corresponds roughly to Gascony in Southwestern France. Before long, her home is invaded by forces of the Catholic Church’s Inquisition. Amicia’s parents are murdered before her eyes and she must flee into the ravaged countryside and nearby villages with her younger brother, the five-year-old Hugo. Taken from the tranquil remove of her home, Amicia journeys through the dilapidated towns and hellish battlefields of a seemingly apocalyptic France. As she explores Guyenne, A Plague Tale forms a portrait of the kind of torment the French experienced during this time.

None of the period’s notable figures are represented in her travels. We don’t see Philip VI, then King of France, or Edward III of England. None of the famous counts and dukes or earls and princes from the era are shown. The closest thing to a display of military glory is a chapter in which Amicia and Hugo traverse the aftermath of an English victory, crossing a battlefield where crows squawk atop mountains of corpses and flaming siege works define a contorted horizon against the grey sky. Rather than depict landmark events from the period, A Plague Tale focuses on ordinary people simply trying to survive the ravages of a war that seems all-consuming. Their allies are a young alchemist, a pair of sibling thieves, an elderly peasant woman, and a grieving blacksmith. Enemies include a fictional Grand Inquisitor and his forces, but also dozens of nameless soldiers and the boiling seas of plague rats that erupt from the ground and swarm across the region, devouring anyone unfortunate enough to wander into their path. A Plague Tale’s story, though based on real history, is unconcerned with great figures and moments of nation-shaping victories and defeats, focusing instead on the idea that the Hundred Years’ War can be best understood as a nightmare whose terrors the majority of France simply tried to endure.

The game’s tone swings wildly between high camp—the Inquisitor and his alchemists all speak of magical, evil plans to control the Plague with the quavering, snivelly tones of Saturday morning cartoon goblins—and a Dantean war travelogue in the mold of grotesque, ground-level Second World War fiction like Elem Klimov’s Come and See or Jerzy Kosiński’s The Painted Bird. As Amicia and Hugo are, for most of their journey, unable to directly confront the Inquisition, English, and French soldiers who seek to kill or capture them, most of the game is spent sneaking around, staying out of sight by ducking behind overturned carts and into the shadows of cobblestoned street corners.

Before an enormously bizarre late-game twist introduces new wrinkles to the narrative, A Plague Tale consists mainly of solving macabre puzzles that often involve extinguishing rodent-prohibiting lights by tossing rocks at patrolling soldiers’ lanterns or knocking corpses into swarms of rats so they’re too busy eating their prey to bother Amicia. (One particularly gruesome scene sees Amicia guide a barnyard pig just befriended by her little brother into a sea of chittering rodents as a distraction. Elsewhere, she does the same to a trapped English soldier, herding the creatures toward him with her torch so he’s devoured by a tidal wave of biting teeth and scraping claws, screaming the whole while.) Nearly everywhere they go, Amicia and Hugo quietly navigate landscapes whose pathways are bordered by mounds of rotting corpses. They scramble through diseased towns piled with the shrouded bodies of plague victims, uncovered mass graves partially filled with the tangled limbs of the dead, and damp medieval alleyways emptying into squares displaying the dozens of townspeople tortured and hanged by the Inquisition on makeshift gibbets. At one point, pursued by enemies, Amicia hides herself from a volley of arrows by burrowing into a pile of French corpses discarded outside an English encampment.

It’s an extraordinarily gruesome game, designed to impress upon the player, with expressionist outrage, that the Hundred Years’ War was not just gleaming armor and heroic speeches, but generations of abject misery for those who lived outside the realms of adventure and chivalry. Rather than clashing swords and courtroom intrigue, it sees knights eaten alive by shrieking rats, the glorious dead left to molder in stinking heaps, Amicia crying out in despair when she must kill a guard by slinging a rock into his head.

counting the dead after the Battle of

Crécy in 1346.

Violins scratch out a racing pulse during the tensest scenes, mournful groans of full string sections backgrounding other moments. The sky, except in moments when the plot requires temporary reprieve, is overcast with wet grey or nauseous ochre clouds. The rats, an indiscriminate force of nature, kill anyone they chance upon. There are no patriotic sentiments. Amicia and Hugo are hunted by both French and English, the game over screens that cap their violent deaths failing to distinguish between contemporary Valois or Plantagenet claims to French rule. The Church provides no solace. It’s represented by torturers who thrive on the despair of their people and the object of A Plague Tales’ pulpiest scenes, a warty old Inquisitor who nourishes his sick body, pointedly enough, with the blood of a young boy.

If A Plague Tale seems excessive—and its cartoonish Inquisition villains and millions of rats and corpses certainly are a lot—it’s also a truer expression of history than a more sanitized look at the early decades of the Hundred Years’ War might have been. In The Hundred Years War: The English in France 1337-1453, historian Desmond Seward describes the spread of the Black Death “all over France during 1348 and 1349” as an event which caused “people [to say] that the end of the world had come.” The mania of A Plague Tale’s Grand Inquisitor is pulp, sure, but his caricature comes from a very real history where the French king Philip VI, “who obviously believed that God was punishing France for her sins … issued an edict against blasphemy” that saw “a man … lose a lip” for a first offense, “for the second the other lip, and for the third the tongue itself.” For religious minorities, especially Western Europe’s Jews, the Plague had even more horrifying results, namely the massacre of entire communities.

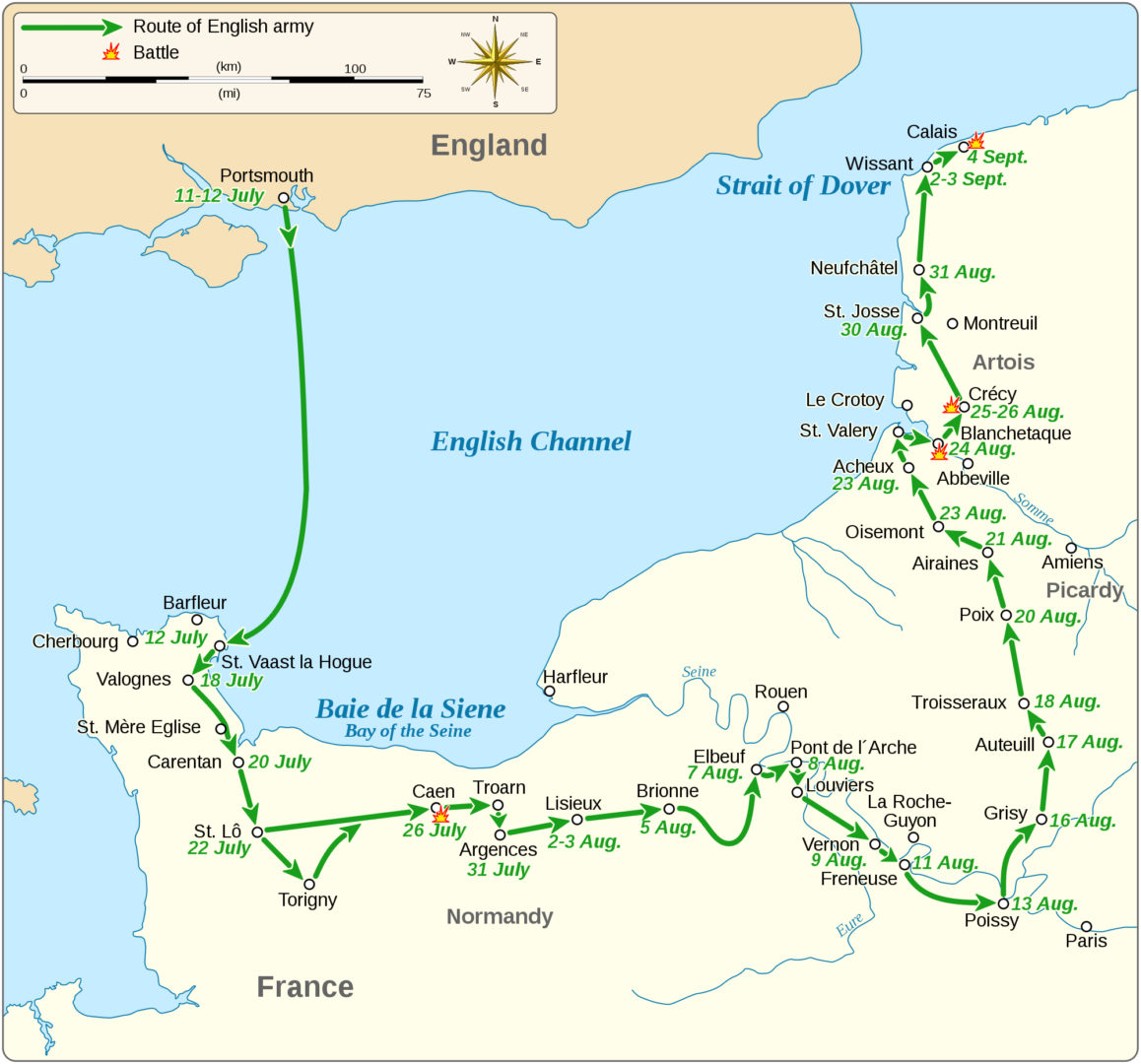

Even before the Black Death began spreading, France had endured nearly a decade of unthinkable atrocities as part of Edward III’s chevauchée campaign. Since 1339, the English strategy involved “[wreaking] as much damage as possible on both towns and country in order to weaken the enemy government.” In practice, as Seward writes, “Every little hamlet went up in flames, each house being looted and then put to the torch. Neither abbeys and churches nor hospitals were spared. Hundreds of civilians—men, women, and children, priests, bourgeois, and peasants—were killed while thousands fled starving to the fortified towns.” Just a few years before A Plague Tale takes place, in a campaign that began in July 1346 and ended with the Truce of Calais, Edward’s forces invaded northern France, leading a chevauchée to “deliberately [devastate] the rich countryside, his men burning mills and barns, orchards, haystacks, and cornricks, smashing wine vats, tearing down and setting fire to the thatched cabins of the villagers, whose throats they cut together with those of their livestock.” Along the way, Seward writes, “One may presume that the usual atrocities were perpetrated on the peasants—the men were tortured to reveal hidden valuables, the women suffering multiple rape and sexual mutilation, those who were pregnant being disemboweled.” He adds, unnecessarily, that “Terror was an indispensable accompaniment to every chevauchée.”

chevauchée campaign.

Credit: Goran tek-en (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The horror of the English assault on France was so great that Pope Clement VI, before beginning to negotiate the (temporary, ineffectual) Truce of Calais, asked King Edward to consider “the sadness of the poor, the children, the orphans, the widows, the wretched people who are plundered and enduring hunger, the destruction of churches and monasteries, the sacrilege in the theft of vessels and ornaments of Divine worship, the imprisonment and robbery of nuns.”

In this light, even A Plague Tale’s most outré moments—its seemingly infinite heaps of corpses, never-ending torrents of rats, and the presence of literally sorcerous characters—can be forgiven as expressionist exaggeration or a magical realist fantasy meant to render the most unbelievable horror of real history into something understandable. Its camp excess is meant to heighten the sense that everything happening to Amicia and Hugo, but also to the wide swaths of ordinary 14th century French who actually lived or died during the horrific medieval war, can only be communicated through the twisting logic of a nightmare.

In games from the Assassin’s Creed, Battlefield, and Call of Duty series (and countless others), history is related through the lens of famous people and events. Whether intentional or not, they subscribe to Thomas Carlyle’s “great man” reading of history, a theory that basically sees the past as having been shaped by the actions of of outsized, greatly influential figures. Games that follow in Carlyle’s footsteps cast those who live less immediately remarkable lives as bit players next to the people and battles that define the broad outline of an era. Centering prominent figures in historical fiction isn’t necessarily wrong, but it’s only a single way to view the complexity of the past—and to try to capture what we can learn from it in the present. There is more to the texture of historical life than the rulers whose decisions determined military and government policy. The ordinary people trying to continue their life while swept up by the whims of the more powerful may not have been the ones declaring wars and signing treaties, but, as the majority of the population, their viewpoint is an essential part of understanding an era. By centering orphaned children surrounded by abstracted despair as its main characters, A Plague Tale offers a more humanistic view of the period’s events than a similar game focused on the great names and battles of the time ever could. As Seward puts it in the introduction to The Hundred Years War, “For the French, unlike the English, the War was more than a mere saga of battles; it was a dreadful experience, which like modern warfare, involved the entire community.”

If the “entire community” suffered the horrors of war, then the only path to depicting it fully is to show what it might have looked like for those so often left nameless by history. A Plague Tale lives up to both its name, and its place in Hundred Years’ War fiction, by so intently working to model this viewpoint, as disgusting, frightening, and bewildering as the result may be.

Header image: Focus Home Interactive

Reid McCarter is a writer and editor based in Toronto. His work has appeared at The AV Club, GQ, Kill Screen, Playboy, The Washington Post, Paste, and VICE. He co-wrote and co-edited the books SHOOTER and Okay, Hero, edits and contributes to Bullet Points Monthly, and tweets @reidmccarter.